Article

citation information:

Żukowska, M., Krasuski, K., Wierzbicki, D. Determining the accuracy

of a digital terrain model based on image data obtained from an unmanned aerial

vehicle. Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport. 2025, 129, 293-309. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2025.129.17

Marta ŻUKOWSKA[1], Kamil KRASUSKI[2], Damian WIERZBICKI[3]

DETERMINING THE

ACCURACY OF A DIGITAL TERRAIN MODEL BASED ON IMAGE DATA OBTAINED FROM AN

UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLE

Summary. This article presents

and describes the results of research on determining the accuracy of a Digital

Terrain Model (DTM) developed based on image data obtained from an Unmanned

Aerial Vehicle (UAV). The Digital Terrain Model was created using image data acquired

by an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, specifically the fixed-wing with electric

propulsion, flying at an altitude of 300 meters. The image data were collected

during a photogrammetric survey conducted over a mountainous area in 2021. The

final elevation values of the Digital Terrain Model were recorded in a GRID

format with a spatial resolution of 5 meters. The article also includes a

comparison of the DTM elevations with results obtained from the satellite GPS

RTK technique. Based on this, an accuracy of elevation determination for

different vertical profiles ranged from 0.19 m to 0.24 m was obtained.

Moreover, the study also involves the development of a DTM from data acquired

by the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle at an altitude of 150 meters. In this case, the

accuracy of determining the elevations of the DTM for different vertical

profiles ranged from 0.10 m to 0.16 m. The results of the research are very

interesting for the application of UAV technology in aerial photogrammetry,

particularly in inaccessible areas, especially mountainous regions.

Keywords: low altitude photogrammetry, DTM, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,

interpolation, accuracy

1.

INTRODUCTION

Due

to the intense development of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technology, these

platforms are increasingly being utilized in the field of photogrammetry. Image

data obtained from UAVs enables the acquisition of a range of fundamental

photogrammetric products that find applications in numerous domains related to

spatial information. Moreover, UAVs, owing to their size, constitute an

excellent photogrammetric tool for conducting surveys over inaccessible areas

such as mountainous terrains [1]. Most such platforms are equipped with

gyroscopic stabilization and allow for autonomous flight missions.

Additionally, the costs associated with such systems and their operational

expenses are significantly lower compared to traditional methods of acquiring

aerial photogrammetric data. A significant limitation of this technology for

low-altitude image data acquisition is the use of cheap, single-frequency GPS

receivers coupled with an INS system. This results in image data being burdened

with several-meter positioning errors, which in turn affects the final accuracy

of the photogrammetric work.

One

of the potential applications of UAVs in aerial photogrammetry is the

generation of a Digital Terrain Model (DTM). A DTM is one of the primary

sources of information about the topographic surface of the terrain,

characterizing the topographic surface through a discrete network of

measurement points with known coordinates (X, Y, Z). When it also includes

information regarding the surface situation, it is referred to as a Digital

Surface Model (DSM). Therefore, a DSM represents the terrain along with its natural

(e.g., trees) or artificial (e.g., buildings) coverage [2],[3]. A DTM can be

generated based on various data sources. Appropriately processed data should

consist of information about the terrain's elevation and accurately represent

its shape. Currently, for the purposes of photogrammetric works, the main

sources of data are field measurements, aerial laser scanning, and image data

from classical aerial photogrammetry [4]. Traditional aerial photogrammetry has

long been the main and simultaneously economical source of topographic surface

elevation data. In the last decade, this role has been taken over by data

obtained through aerial laser scanning LIDAR, and the ability to develop large

areas necessitates particular attention to this method. A significant advantage

of LIDAR is that some laser pulses reflect off the terrain coverage surface,

such as forest canopies, while some (about 30% in summer and 70% in winter)

penetrate vegetation and reflect off the topographic surface, providing

information about the height of terrain coverage elements and the ability to

generate both DTM and DSM [5]. As LIDAR technology remains expensive, many

countries prefer to create photogrammetric products like DTM from images

acquired with UAVs. In recent years, small UAVs equipped with imaging sensors

offer a low-budget form of acquiring low-altitude image data, which can then be

processed into a dense point cloud using the Structure from Motion (SfM) algorithm family [6], [7]. This allows for the

generation of DTMs and DSMs and, consequently, one of the main products of

low-altitude photogrammetry – orthophotomaps.

1.1. Related

works

In

the literature, there are numerous studies on the accuracy analysis of Digital

Terrain Models (DTMs) generated based on images acquired from low altitude. In

the research conducted by Udin et al. [8], the accuracy of a DTM created from

UAV images captured with a non-metric Canon PENTAX W90 camera was examined. The

study established a photogrammetric network consisting of 23 points with known

X, Y, and Z coordinates. Sixteen of these were used as ground control points

(GCPs), and seven as independent check points (ICPs) to assess accuracy. The

analysis of the DTM accuracy was based on the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of

the Z-coordinate, obtaining an accuracy of less than one meter. In the work of

Akturk et al. [1], the accuracy of a DTM for areas with varied terrain was

investigated using UAV image data. The results indicated that the DTM accuracy

(RMSE value) was 0.57 m. The use of ground control points during the DTM

generation process reduced the RMSE value by 0.06 m. Uysal et al. evaluated the

DTM accuracy using 30 control points and achieved a total vertical accuracy of

0.062 m at a flying height of 60 m. The findings demonstrate that UAV

photogrammetry data can achieve suitable accuracy, very similar to RTK GPS

data, thus enabling the use of UAV photogrammetric data for creating maps,

geodetic measurements, and other engineering applications at low cost, time

savings, and minimal fieldwork. Additional studies [9] on DTM accuracy have

proven that factors such as flight planning, fieldwork, camera settings on the

UAV platform, and an adequate number of ground control points can enhance the

accuracy of the generated terrain models. In research by Jamalulizam

et al. [10], the accuracy of a DTM based on UAV data acquired at various flight

altitudes was examined, concluding that a flight altitude of 300 m provides a

more accurate terrain surface model compared to a flight altitude of 400 m.

1.2. Research

Purpose

The paper is structured as follows: in Section 2 the

research method is explained. Section 3 presents the material and experimental

results. In Section 4 the results are discussed. Finally, Section 5 provides a

brief summary of this work.

2. METHODS

The process of generating a Digital Terrain Model

(Fig. 1) based on data acquired from the UAV consists of the following steps:

data import into specialized software, image adjustment, georeferencing of

images using check points to optimize camera position and orientation, dense

point cloud generation, point cloud filtering (feature classification), DTM

generation, DSM generation and orthomosaic creation.

Fig.

1. Workflow to generate DTMs

3. MATERIALS

AND EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

3.1. Study

area

Image

data for the research experiment was acquired using a fixed-wing system

equipped with a Sony camera. The photogrammetric raid was carried out in March

2021 under moderate photographic conditions. The test area was the vicinity of

the town (Małopolskie Voivodeship) in southern

Poland.

Ten ground control points and five check points were

used for the analyses. All points were signaled, and their coordinates were

determined using the GPS RTK technique with an accuracy of no worse than 0.05 m

(mountainous terrain). The test block consisted of 100 images acquired from an

altitude of 300 m (see Fig. 2). The aerial images were arranged in 10 strips

and the field pixel size was 0.10 m.

Image

data processing was performed in the commercial software UASMaster

[11]. After automatic digital aerotriangulation, the

mean-square error value of a typical observation was 5.1 µm (1.1 pixels). For

the check points, the mean square error values for the X, Y, and Z coordinates

were 0.10 m, 0.12 m and 0.23 m, respectively. In a further step, a dense point

cloud was generated, which was then subjected to a filtering process. The

generated Digital Terrain Model was saved as a regular GRID screen with a spatial

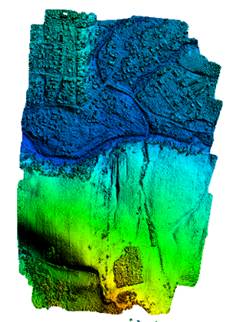

resolution of 5 m (see Fig. 3).

Fig.

2. The visualization of the test photogrammetric block – altitude 300 m

Fig.

3. The visualization of the test photogrammetric block – altitude 300 m

Tab. 1

Parameters

of the test block

|

DTM development area |

0.9 km2 |

|

Form of DTM presentation |

regular GRID |

|

Number of GRID nodes |

34666 |

|

Density of points |

4 points /

25 m2 |

|

Mesh |

5 m |

|

Average elevation |

642.40 m |

|

DTM height

range |

from 604.02 m to 732.06 m |

Table

1 shows the basic parameters of the DTM compiled from aerial imagery from the

UAV platform. The size of the DTM compilation was approximately 0.9 km2,

assuming a point density of 4 points per 25 m2. The total number of

GRID grid node points in the DTM was 34666 for a grid

mesh of 5 m. In addition, the average height of the DTM was 642.40 m, with

ground denivelations ranging from 604.02 m to 732.06 m.

3.2.

Experimental results

This

chapter presents the results of a comparison of selected DTM profiles whose

heights were determined by an interpolation model and by GPS RTK satellite

measurements. A total of three field profiles of DTM heights were analyzed. For

the interpolation model, the nearest neighbor method was used, where the

heights of the interpolated profile points were determined based on a weighted

average, as follows:

![]() (1)

(1)

where:

![]() –

interpolated height for a given profile point,

–

interpolated height for a given profile point,

![]() –

weight,

–

weight,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() – plane rectangular coordinates of the profile

point for which the height is being interpolated,

– plane rectangular coordinates of the profile

point for which the height is being interpolated,

![]() – rectangular planar coordinates of a

neighboring point on the regular GRID grid,

– rectangular planar coordinates of a

neighboring point on the regular GRID grid,

![]() –

serial number,

–

serial number,

![]() – number of points used to interpolate a

single height,

– number of points used to interpolate a

single height,

![]() – height of a

neighboring point from the regular GRID grid.

– height of a

neighboring point from the regular GRID grid.

The

interpolation process selects neighboring points with

coordinates ![]() , whose

distance from the interpolated point

, whose

distance from the interpolated point ![]() is less than 5 m, i.e. the mesh of the regular

GRID. The weight parameter in formula (1) is defined as a function of the

inverse distance [13] and expressed in the unit [1/m2]. The heights

of neighboring points from the regular GRID mesh are

given in meters.

is less than 5 m, i.e. the mesh of the regular

GRID. The weight parameter in formula (1) is defined as a function of the

inverse distance [13] and expressed in the unit [1/m2]. The heights

of neighboring points from the regular GRID mesh are

given in meters.

In

the second survey method, the coordinates of the selected DTM profiles were

measured using GNSS satellite technology for the GPS RTK difference method. In

the GPS RTK method, user coordinates are determined by dual-frequency phased

GPS observations at L1/L2 frequencies using a double-difference technique. In

the research test, a Leica Viva L1/L2 satellite receiver was used to measure

the pickets in the field. The typical accuracy of the terrain elevation

coordinate determination was approximately 0.05 m. The GPS RTK solution used

correction corrections from the state-owned ASG-EUPOS receiver network.

Figures

5, 6, and 7 show a diagram of the distribution of measured control points for

verification of DTM height determination. For profile no. 1, 32 pickets were

measured over an area of approximately 0.3 km2. On the other hand,

for profile no. 2, 51 pickets were measured over an area of approximately 0.005

km2. However, for profile no. 3, 39 pickets were measured over an

area of approximately 0.002 km2.

Fig. 4. The

measurement points of profile no. 1 in the testing area

Figures

7, 8 and 9 show the DTM profile height values based on the interpolation model

and the GPS RTK method. The scatter of the obtained DTM profile height results

for the interpolation model is:

-

from 608.35 m to 686.01 m for profile no. 1,

-

from 643.19 m to 651.78 m for profile no. 2,

-

from 644.27 m to 692.80 m for profile no. 3.

For

the GPS RTK method, the scatter of DTM profile height results is respectively:

-

from 608.46 m to 686.02 m for profile no. 1,

-

from 643.01 m to 651.77 m for profile no. 2,

-

from 644.20 m to 692.70 m for profile no. 3.

Fig. 5. The

measurement points of profile no. 2 in the testing area

Fig. 6. The

measurement points of profile no. 3 in the testing area

Figures

10, 11 and 12 then present the height difference of the measured DTM profile

based on the interpolation model and the GPS RTK method. The value of the

difference was determined based on the relationship:

![]() (2)

(2)

where:

![]() –

altitude from the GPS RTK measurement for a given profile point.

–

altitude from the GPS RTK measurement for a given profile point.

Fig. 7. The

elevation of profile no. 1 in the interpolation model and GPS RTK method

Fig. 8. The

elevation of profile no. 2 in the interpolation model and GPS RTK method

In

addition, for height difference dH, accuracy

parameters were determined in the form of mean absolute error ![]() and mean

squared error

and mean

squared error ![]() as recorded below:

as recorded below:

![]() (3)

(3)

and

![]() (4)

(4)

where:

![]() –

number of all measured pickets.

–

number of all measured pickets.

Fig. 9. The

elevation of profile no. 3 in the interpolation model and GPS RTK method

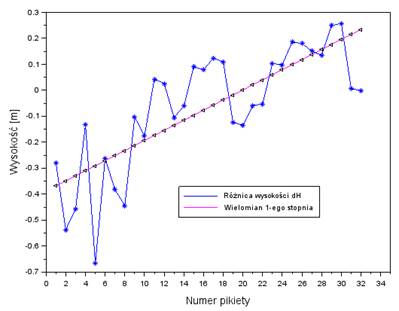

Fig. 10. The

elevation difference of profile no. 1 between the interpolation model

and GPS RTK method

For

profile no. 1 (Fig. 11), the average value of the dH

parameter is equal to -0.07 m, with the scatter of the dH

parameter results ranging from -0.67 m to almost 0.26 m. The error value of ![]() is equal to

0.24 m, while the parameter

is equal to

0.24 m, while the parameter ![]() is equal to

0.18 m.

is equal to

0.18 m.

On

the other hand, for profile no. 2 (Fig. 12), the average value of the dH parameter is equal to 0.12 m, with the scatter of

the dH parameter results ranging from -0.20 m to

almost 0.41 m. The error value of ![]() is equal to 0.19 m, while the

is equal to 0.19 m, while the ![]() parameter is equal to 0.16 m.

parameter is equal to 0.16 m.

In

addition, for profile no. 3 (Fig. 12), the average value of the dH parameter is equal to 0.14 m, with the scatter of

the dH parameter results ranging from -0.26 m to

approximately 0.60 m. The error value of ![]() is equal to 0.21 m, while the parameter

is equal to 0.21 m, while the parameter ![]() is equal to 0.15 m.

is equal to 0.15 m.

Fig. 11. The

elevation difference of profile no. 2 between interpolation model

and GPS RTK method

Fig. 12. The

elevation difference of profile no. 3 between the interpolation model

and GPS RTK method

4. DISCUSSION

The

discussion chapter is divided into three parts. In the first part, the trend of

change of the DTM height difference was determined in the form of a linear

regression. In the second part, the repeatability of the proposed test

methodology for the images obtained from the 150 m altitude was performed. The

third part of the discussion is a comparison of the obtained survey results in

relation to the literature on the subject.

In

the first part of the discussion, Figures 15, 16 and 17 show the nature of the

variation of the parameter dH in the form of a

1st-degree polynomial (linear regression function), which is described by the

relation [13]:

![]() (5)

(5)

where:

![]() – next picket number,

– next picket number,

![]() – linear coefficients of the 1-degree

polynomial determined.

– linear coefficients of the 1-degree

polynomial determined.

Fig. 13. The

linear regression of values of the ![]() parameter from profile no. 1

parameter from profile no. 1

Fig. 14. The

linear regression of values of the ![]() parameter from profile no. 2

parameter from profile no. 2

The

determined coefficients (a,b) from equation

(5) are obtained by applying the method of least squares taking into account

the values of dH for all measured pickets. For

profile no. 1, the nature of the changes in the parameter is positive, as evidenced by the

value of the linear parameter "a" equal to 0.019. The value of the

parameter "b" is negative and equal to -0.387 m for the measurements

adopted in the calculations. The error of fit of the linear regression function

against the actual values of dH is 0.14 m.

Furthermore, the distribution of corrections during the numerical calculations

ranged from -0.22 m to 0.38 m. Subsequently, for profile no. 2, the nature of

the changes in the parameter dH is negative

and the values of the linear coefficients are a= -0.007 and b= 0.303,

respectively. The error of fit of the linear regression function with respect

to the actual values of dH is 0.11 m and the

distribution of the corrections is described by the range of values (-0.25 ÷

0.16) m. Then, for profile no. 3, the nature of the changes in the dH parameter is positive, and the values of the linear

coefficients are a= 0.001 and b= 0.118, respectively. The error of fit of the

linear regression function with respect to the actual values of dH is 0.16 m, and the distribution of the

corrections is described by a range of values from -0.47 m to 0.39 m. The final

obtained statistical values of the 1st-degree polynomial parameters for the

individual DTM profiles are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 15. The

linear regression of values of the ![]() parameter from profile no. 3

parameter from profile no. 3

Tab. 2

The

characteristic of parameters of linear regression for all DTM profiles

|

Profile |

Linear coefficients

[m] |

Distribution of amendments

[m] |

Fitting

error of linear regression [m] |

|

No. 1 |

a= 0.019 b= -0.387 |

-0.22 ÷ 0.38 |

0.14 |

|

No. 2 |

a= -0.007 b= 0.303 |

-0.25 ÷ 0.16 |

0.11 |

|

No. 3 |

a= 0.001 b= 0.118 |

-0.47 ÷ 0.39 |

0.16 |

The

second part of the discussion was to determine the accuracy of the DTM

generated from aerial photographs acquired from an altitude of 150 m. Figures

17, 18 and 19 show the difference in DTM height from interpolation and GPS RTK

measurements for the first profile. In addition, the errors ![]() and

and ![]() were calculated.

were calculated.

Fig. 16. The

elevation difference of profile no. 1 between the interpolation model

and GPS RTK method for altitude150 m

Fig. 17. The

elevation difference of profile no. 2 between the interpolation model

and GPS RTK method for altitude150 m

Fig 18. The

elevation difference of profile no. 3 between the interpolation model

and GPS RTK method for altitude150 m

For

Profile no. 1, the scatter of results of the dH

parameter ranges from -0.31 m to about 0.58m. The error value of ![]() is equal to

0.11 m, while the parameter

is equal to

0.11 m, while the parameter ![]() is 0.16 m. Next, for profile No. 2, the

results of dH

difference were from -0.22 m to about 0.22 m, and the individual errors are

is 0.16 m. Next, for profile No. 2, the

results of dH

difference were from -0.22 m to about 0.22 m, and the individual errors are ![]() =0.09 m,

=0.09 m, ![]() =0.10 m.

Finally, for profile no. 3, the values of the dH parameter ranged from -0.41 m

to about 0.41 m, and the individual errors are

=0.10 m.

Finally, for profile no. 3, the values of the dH parameter ranged from -0.41 m

to about 0.41 m, and the individual errors are ![]() =0.12 m,

=0.12 m, ![]() =0.15 m. Table

3 shows the summary comparison of

=0.15 m. Table

3 shows the summary comparison of ![]() and

and ![]() errors obtained in the process of DTM

development for image data acquired from 150 m and 300 m altitude. Based on the

obtained results of

errors obtained in the process of DTM

development for image data acquired from 150 m and 300 m altitude. Based on the

obtained results of ![]() and

and ![]() errors, it can be said that:

errors, it can be said that:

-

the accuracy expressed by the ![]() parameter increased from 20% to 44% when using

image data at the 150 m altitude than from the 300 m altitude,

parameter increased from 20% to 44% when using

image data at the 150 m altitude than from the 300 m altitude,

-

the accuracy expressed by the ![]() parameter increased from 28% to 47% when using

image data at the 150 m altitude than from the 300 m altitude.

parameter increased from 28% to 47% when using

image data at the 150 m altitude than from the 300 m altitude.

Tab. 2

Characteristics

of the accuracy of the DTM developed from

aerial photographs acquired from 150 m and 300 m altitude

|

Profile |

Height 300 m |

Height 150 m |

|

No. 1 |

|

|

|

No. 2 |

|

|

|

No. 3 |

|

|

The

final stage of the discussion concerns the comparison of the results and the

presented research method in relation to the analysis of the state of the art.

Referring

to the results presented in the article and comparing them with other

publications concerning the accuracy of Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) obtained

using low-altitude photogrammetry, several important similarities can be

observed. When compared to studies presented in publications such as [14],

similar challenges and opportunities associated with the use of UAVs in

photogrammetry are apparent. Our study indicates the effectiveness of the

weighted average method for interpolating heights from a GRID network, which

aligns with the findings of other works [6], where the accuracy of models

obtained using this method is also emphasized in comparison to standard

geodetic techniques like RTK GPS.

In

our study, where the experiment was conducted on a sample of 51 points, an

average height difference of -0.02 m and an RMS error of 0.11 m are indicators

of good quality DTM interpolation. A similar study presented in [5] also

demonstrated that low-cost UAV photogrammetry could provide sufficient accuracy

for many applications, although it highlighted the need to consider terrain

specifics, such as vegetation or topography.

The

values of the linear coefficients (a, b) determined in our study for

different profiles show that the nature of terrain height changes can vary

depending on the specifics of the measurement location. This observation is

significant in the context of discussions on DTM creation methodology and

accuracy assessment, as different areas may require the interpolation method to

be adjusted to the data specificity.

5. CONCLUSION

The

article demonstrates the feasibility of using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

technology, for determining the height of a Digital Terrain Model (DTM) from

images acquired at an altitude of 300 meters. The DTM was developed as an

additional product of digital aerotriangulation for

the aerial photographs obtained. The DTM coordinates for a regular 5 m GRID

were used to determine the terrain profile height, which was also measured

using GPS RTK technique. The research experiment was conducted on a sample of 51

measured points. The terrain profile height values were interpolated from the

regular GRID using the weighted average method and compared with the solution

obtained using the GPS RTK technique. The average difference in terrain profile

height from the comparison was -0.02 m, with an RMS error of 0.11 m.

Additionally, the work describes changes in the height difference parameter of

the profile using a first-degree polynomial function, with a polynomial fitting

error relative to the determined height difference values of 0.09 m.

Future

perspectives for the development of the presented methodology for determining

the accuracy of the DTM based on UAV image data could consider several avenues.

Firstly, it would be beneficial to investigate the impact of different

atmospheric and seasonal conditions on the quality of image data and their

effect on DTM accuracy. It is possible that data acquired at different times of

the year or under various lighting conditions could influence the results of

terrain height interpolation.

Secondly,

the application of advanced image processing algorithms and machine learning

techniques could improve the automation of the DTM creation process and enhance

its precision. In particular, these techniques could assist in better

identifying and eliminating potential errors and anomalies in image data.

A

third perspective involves the use of a greater number of independent check

points (ICPs) measured with GPS RTK technique, which could improve model

calibration and increase the accuracy of interpolation. Experiments with

different GRID sizes and the application of other interpolation methods, such

as kriging or splines, may also yield valuable results.

Moreover,

future research could focus on optimizing and automating the entire measurement

and computation process to further reduce the time required to develop DTMs and

decrease the costs associated with such studies.

References

1.

Erdal

Akturk, Aykut Ozan Altunel. 2019. „Accuracy assessment of a low-cost UAV

derived digital elevation model (DEM) in a highly broken and vegetated

terrain”. Measurement 136: 382-386. ISSN: 0263-2241. DOI:

10.1016/j.measurement.2018.12.101.0.

2.

Guth P.L., A. Van Niekerk, C.H. Grohmann, J-P. Muller, L. Hawker, I.V. Florinsky, D. Gesch, H.I. Reuter, V. Herrera-Cruz, S. Riazanoff,

et al. 2021. „Digital

Elevation Models: Terminology and Definitions”. Remote Sensing 13(18): 3581. DOI: 10.3390/rs13183581.

3.

Eltner

Andreas, Lars Kaiser, Carlos Castillo, Gregory Rock, Franz Neugirg, Antonio Abellán. 2016. „Image-based surface reconstruction in

geomorphometry-Merits, limits and developments”. Earth Surf. Dyn. 4:

359-389.

4.

Kosmatin

Fras Miha, Aljoša Kerin, Matevž Mesarič, Vid Peterman, David Grigillo. 2016.

„Assessment of the Quality of Digital Terrain Model Produced from Unmanned

Aerial System Imagery International Archives of the Photogrammetry”. Remote

Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences XLI-B1: 893-899. DOI: 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLI-B1-893-2016.

5.

Jiménez-Jiménez

Sergio Iván, Wilmer Ojeda-Bustamante, Manuel David Javier Marcial-Pablo, José

Enciso. 2021. „Digital terrain models generated with low-cost UAV

photogrammetry: Methodology and accuracy”. ISPRS International Journal of

Geo-Information 10(5): 285. DOI:

10.3390/ijgi10050285.

6.

Sanz‐Ablanedo

Eduardo, John H. Chandler, Pablo Ballesteros‐Pérez, José R.

Rodríguez‐Pérez. 2020. „Reducing systematic dome errors in digital

elevation models through better UAV flight design”. Earth Surface Processes

and Landforms: 45(9): 2134-2147.

7.

Long Nicolas, Bernard Millescamps, Benjamin Guillot, Frédéric

Pouget, Xavier Bertin. 2016. „Monitoring the topography of a dynamic tidal

inlet using UAV imagery”. Remote Sensing 8(5): 387.

8.

Wan

Shamsuddin Udin, Hassan Abdal Fattah, Ahmad Aizuddin, Tahar Noorazman. 2012.

„Digital Terrain Model extraction using digital aerial imagery of Unmanned

Aerial Vehicle”. In: IEEE

8th International Colloquium on Signal Processing and its Applications: 272-275. Malacca, Malaysia. 23-25 March. DOI:

10.1109/CSPA.2012.6194732.

9.

Leal-Alves

Dione C., José Weschenfelder, Maria de Lourdes Albuquerque, et al. 2020.

„Digital elevation model generation using UAV-SfM photogrammetry techniques to

map sea-level rise scenarios at Cassino Beach”. SN Appl. Sci.

2: 2181, DOI: 10.1007/s42452-020-03936-z.

10.

Mohd Zain

Jamalulizam, Wan Mohamed Wan Mat, Norezan Nazri Nordin Mohd, Sulaiman Shahid

Ali, Ma'arof Irwan, Samad Ahmad Mohd. 2022. „DSM and DTM Extraction Accuracy

Detection Utilising UAV Imagery on Different Altitudes”. In: IEEE

13th Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC). Shah Alam, Malaysia, 16-20 August. DOI:

10.1109/ICSGRC55096.2022.9845130.

11.

UAS Master Tutorial for Version 11.0 and higher. 2020.

Trimble Germany.

12.

Zhu Y.,

X. Liu, J. Zhao, Zhao, J. Zhao, X. Wang, D. Li. 2019. „Effect of DEM interpolation neighbourhood on terrain

factors”. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information

8(1): 30.

13.

Osada Ewa. 2001. Geodezja.

[In Polish: Geodesy]. Wrocław University of

Science and Technology Publishing House. ISBN: 83-7085-663-2.

14.

Uysal Mustafa,

Ahmet S. Toprak, Nedim Polat. 2015. „DEM generation with UAV Photogrammetry and

accuracy analysis in Sahitler hill”. Measurement 73: 539-543. ISSN: 0263-2241. DOI: 10.1016/j.measurement.2015.06.010.

Received 16.06.2025; accepted in revised form 08.09.2025

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License