Article

citation information:

Nguyen,

N.H.Q., Nguyen, N.Q.N., Nechaev, V.N. Optimizing alternative air traffic service

routes for airport disruption contingency management. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series

Transport. 2025, 129, 169-190. ISSN:

0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2025.129.10

Ngoc Hoang Quan NGUYEN[1],

Ngoc Quynh Nhu NGUYEN[2],

Vladimir Nikolaevich NECHAEV[3]

OPTIMIZING

ALTERNATIVE AIR TRAFFIC SERVICE ROUTES FOR AIRPORT DISRUPTION CONTINGENCY

MANAGEMENT

Summary. Flight disruptions due

to destination airport unavailability present significant challenges for air

traffic management and airline operations. These situations may lead to

cascading delays, increased fuel consumption, and reduced passenger

satisfaction. A key response strategy is the timely identification of

alternative air traffic services (ATS) routes to suitable diversion airports

while ensuring flight safety and operational continuity. However, existing

diversion approaches often rely on static contingency plans or real-time

decisions by air traffic controllers, which may not perform well under dynamic

conditions. To address this, a robust multi-objective optimization model based

on the A-star algorithm is proposed to dynamically identify optimal alternative

air traffic services routes when the planned destination becomes inaccessible.

The model accounts for multiple objectives, including route efficiency, safety,

and operational feasibility, across pre-tactical and tactical phases of air

traffic flow management. By integrating airspace constraints and traffic flow

considerations, the model supports adaptive, data-informed decision-making.

Simulation results demonstrate the model’s ability to reduce network

disruptions and support safe, efficient diversions under various traffic

scenarios. This study contributes to enhancing the resilience of the air

transportation system and provides a foundation for future integration into

intelligent air traffic management tools and decision support systems.

Keywords: alternative ATS route, air traffic management, destination airport

unavailable, A* algorithm, multi-objective optimization model

1.

INTRODUCTION

Air transportation is a cornerstone of global

connectivity, but it is inherently vulnerable to disruptions caused by adverse

weather, technical malfunctions, security threats, and other unforeseeable

events. In the event of airport inoperability, aircraft must be promptly

reassigned to alternative destinations through optimized ATS routing to ensure

safety, reduce economic impact, and sustain operational continuity

Recent statistical data underscores the

significance of this issue. According to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation

Statistics (BTS, 2025), a total of 15,059 flights operated by the ten major

airlines were diverted to alternate airports in 2024 alone, compared to 14,864

in 2023. Similarly, data from Eurocontrol (2024) reveals that in 2022, out of

9.3 million flights within the EUROCONTROL Network Manager area, 28,738 flights

(0.3%) landed at an airport different from their originally intended

destination, and the estimated cost per diverted flight was approximately

€8,800. In addition to direct operational costs, unplanned diversions impose

significant financial burdens on airlines, airports, and passengers. According

to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA, 2020), the variable operating cost

per flight hour is $1,508, while the average cost of a flight cancellation per

passenger is approximately $15.51. These figures, when multiplied across

thousands of diverted flights annually, represent substantial economic losses

for the aviation industry. Beyond monetary considerations, flight diversions

also contribute to logistical challenges, including increased air traffic

congestion, additional fuel consumption, crew scheduling complexities, and

passenger inconvenience. Moreover, flight diversions cause ripple effects

beyond immediate disruptions. They can delay connecting flights, burden ATC and

alternate airports, and strain limited resources. Prolonged ground delays and

passenger reallocation may also damage airline reputation and customer loyalty,

with lasting impacts on passenger behavior.

Although diverted flights account for a small

portion of total operations, their cumulative impact on ATM efficiency and

safety is significant. This underscores the need for advanced strategies to

identify alternative ATS routes, supported by real-time adaptive ATM systems

and predictive analytics. Emerging approaches increasingly rely on optimization

models powered by AI and advanced algorithms, enabling real-time disruption

prediction and route optimization. However, despite their promise, the application

of such innovations to the dynamic selection of alternative ATS routes remains

an underexplored area. Most existing studies tend to address peripheral topics

rather than directly confronting this critical challenge.

Several notable studies have explored

optimization techniques relevant to trajectory adjustments. Xu et al. (2020)

proposed a collaborative ATFM framework utilizing Mixed-Integer Linear

Programming to optimize cost-efficient trajectory adjustments and minimize

delays for airspace users. Similarly, Yang et al. (2021) introduced a robust

optimization model designed to enhance adaptability and efficiency in

identifying alternative ATS routes for flights under uncertain adverse weather

conditions. Another study focused on a robust optimization framework for flight

diversions under uncertainty, balancing stakeholder interests with operational

performance (Bongo and Sy, 2020). However, the aforementioned studies primarily

focus on optimizing real-time or pre-tactical trajectory adjustments for

aircraft, rather than developing a comprehensive optimization framework capable

of determining alternative routes when the original ATS route becomes

unavailable. More notably, there is a near absence of research dedicated to

identifying alternative routes when the original destination airport (or

transfer of control point) is rendered unusable. This gap highlights a

promising research direction focused on developing an advanced optimization

model that can dynamically identify alternative ATS routes across different

phases of ATFM (pre-tactical, or tactical), while satisfying specific

operational constraints and performance objectives.

In light of these challenges, it is essential to

develop an optimized decision-support framework for identifying alternative ATS

routes when the planned destination airport becomes unavailable. This study

proposes a robust model based on the A* algorithm to determine the most

efficient route to an alternate airport under two cases. The first involves the

unavailability of the destination airport alone – due to technical issues or

on-ground incidents – while the second addresses broader disruptions, including

surrounding airspace and portions of the original route (hereafter referred to

as the No-fly Area), as seen in adverse weather or airspace restrictions. These

cases present varying levels of complexity, particularly in maintaining

regulatory compliance and safety. In both cases, the model aims to minimize

total flight distance to ensure operational efficiency and feasibility.

To address the added complexity of the second

case, three routing scenarios with additional sub-objectives are introduced:

(1) minimizing deviation from the original route, (2) minimizing the total

distance from the original start to the new destination, and (3) enabling

user-defined preferences for flexible routing. These scenarios enhance the

model’s practical applicability across different ATFM phases. Scenarios 1 and 2

are best suited for pre-tactical planning, where minimizing flight time

(Scenario 2) or maintaining route consistency (Scenario 1) supports efficiency

and conflict avoidance. Scenario 3, offering flexible user input, is more

appropriate for the tactical phase, which requires real-time responsiveness to

actual traffic and airspace conditions.

To evaluate the efficiency and responsiveness of

the proposed model in dynamically identifying alternative ATS routes, the ATS

route network within the HCM FIR has been selected as the primary case study.

The HCM FIR holds a strategically significant geographical position (Carreras

and Greenman, 2017; Nguyen Le Quyen, 2022), serving as a critical aviation hub

that connects countries in the Northern Hemisphere – particularly Russia and

China – to those in the Southern Hemisphere, including Oceania. Additionally,

it borders the vast South China Sea, a region that accommodates multiple

crucial international ATS routes. In addition to its strategic location,

Vietnam has one of the fastest-growing aviation industries in the world

(International Trade Administration, 2024; 6Wresearch, 2022). The country’s air

transport sector has experienced significant expansion in recent years, driven

by increasing passenger demand, economic growth, and enhanced connectivity with

global markets. The HCM FIR plays an essential role in facilitating this

growth, serving as a critical gateway for both domestic and international air

traffic. Another key factor that underscores its significance is the relatively

high air traffic density on several routes within the FIR. For instance, the

HCM – Hanoi route, which largely falls within this FIR, ranks as the fourth

busiest domestic air route in the world (OAG, 2024). Furthermore, the weather

conditions in this region can be highly complex at times due to the influence

of monsoons and tropical storms originating from the South China Sea. These

adverse weather patterns frequently disrupt flight schedules, requiring not

only frequent ATS route reconfigurations but also necessitating aircraft

diversions to alternate airports. A notable example occurred on May 16,

2023, when seven flights originally scheduled to land at Tan Son Nhat

International Airport were unable to do so and had to divert to alternate

airports due to unfavorable weather conditions (Vietnamplus, 2023). Given these factors, selecting the HCM

FIR as a case study is highly appropriate, as it ensures both practical

relevance and a robust scientific foundation. Moreover, the insights gained

from this analysis can enhance the potential for broader implementation in

other high-density airspaces worldwide, particularly in regions where adverse

weather conditions frequently necessitate the identification of alternative ATS

routes and airport diversions.

2.

METHODOLOGY FOR OPTIMIZING ALTERNATIVE ATS ROUTES DURING AIRPORT DIVERSIONS

2.1. A*

algorithm

The

A* algorithm is one of the most widely used and efficient pathfinding

algorithms in computer science and artificial intelligence. It is a heuristic

search algorithm that extends Dijkstra’s Algorithm by incorporating heuristic

information to improve efficiency (Beeker, 2004). The fundamental principle of

A* is to find the shortest route between a start node and a goal node in a

weighted graph while balancing exploration and optimality. A* operates using a cost function:

![]()

where:

g(n)

represents the actual cost from the start node to node n,

h(n) is

the heuristic estimate of the cost from 𝑛 to

the goal,

f(n) is

the estimated total cost of the path through node 𝑛.

The

choice of heuristic function significantly influences the performance of A*,

with an admissible (never overestimates the true cost) and consistent (follows

the triangle inequality) heuristic ensuring both optimality and efficiency.

Compared to uninformed search methods, A* intelligently prioritizes promising

paths, reducing unnecessary exploration and enhancing computational speed. It

guarantees an optimal solution if the heuristic function does not overestimate

the actual cost. This characteristic makes A* particularly effective in solving

shortest route problems in large-scale environments. The algorithm’s ability to

balance accuracy and efficiency has made it a fundamental tool in artificial

intelligence and operations research. Its scalability and robustness ensure its

continued relevance in modern computational problem-solving, making it one of

the most powerful techniques for optimal pathfinding in complex systems,

including transportation networks (Felix et al, 2024; Wang et al., 2024),

robotic navigation (Ju et al, 2020; Kabir et al, 2024), and game environments

(Kurniawan et al, 2024), where real-time decision-making and adaptability are

crucial for efficiency and performance.

In

the field of aviation in general and ATM in particular, the A* algorithm has

been widely applied to determine optimal flight routes for both manned civil

aircraft (Ma et al. 2022; Neretin et al. 2021; Li et

al. 2023; Roy, 2023) and unmanned aerial vehicles (Mandloi

et al. 2021; Ji et al. 2024). However, most existing studies focus on initial

trajectory planning rather than the dynamic re-routing of ATS paths under

operational constraints. This research addresses that gap by proposing a

re-routing model capable of optimizing alternative ATS routes while ensuring

efficiency and regulatory compliance. Designed for use across pre-tactical and

tactical phases, the model adapts to diverse scenarios and disruptions,

enhancing the flexibility and resilience of ATS route planning in complex

airspace environments.

2.2. Steps for

Developing Optimization Models and Mathematical Models

Since the A-Star (A*) algorithm

is a branch of graph theory, the airspace structure in this study is

represented as a graph G = (N,O) where ![]() , and

, and ![]()

![]() . In this representation, N

consists of waypoints and airport coordinates (collectively referred to as

nodes), while 𝑂 represents the arcs, each

defined as a direct connection between two nodes. Each arc 𝑂 is characterized by two key

parameters: distance (𝑑) and angle (𝜃).

. In this representation, N

consists of waypoints and airport coordinates (collectively referred to as

nodes), while 𝑂 represents the arcs, each

defined as a direct connection between two nodes. Each arc 𝑂 is characterized by two key

parameters: distance (𝑑) and angle (𝜃).

A crucial aspect of data

preprocessing is ensuring the accurate input of node coordinates, as precise

spatial representation is fundamental for effective route optimization. To

achieve this, the latest aeronautical data from the Vietnam AIP 2024 is utilized,

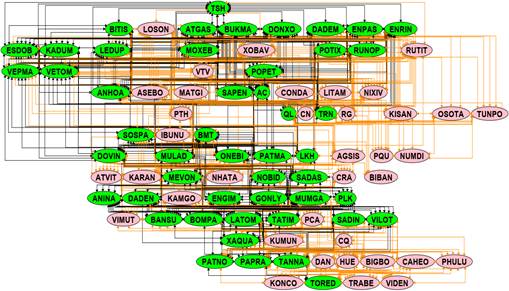

incorporating a total of 130 nodes into the airspace model. Figure 1

illustrates the spatial relationships among these nodes, providing a graphical

representation of the airspace network structure.

Fig. 1. Illustrating the Structure of Airspace

in the Model

and Establishing Relationships Between Nodes

After

completing the airspace structure description using nodes, the next step is to

establish relationships between them, specifically defining parent-child

connections. This hierarchical relationship is essential for optimizing route

search processes. Given that the HCM FIR encompasses both land and sea areas,

the airspace structure is systematically divided into two distinct regions:

land–coast and coast-sea. To determine how nodes are connected, a systematic

selection process is applied. Each node identifies neighboring

nodes within a specified radius, forming a structured network. The node at the center of this defined area is designated as the parent

node, while all surrounding nodes that fall within the radius are considered

child nodes. A directional scanning technique is used, where the search is

conducted in one-degree increments. In each direction, at most one child node

is selected, ensuring an even distribution of connections and preventing

unnecessary redundancy. This method enhances the efficiency of route

calculations and ensures a well-structured node hierarchy for optimal airspace

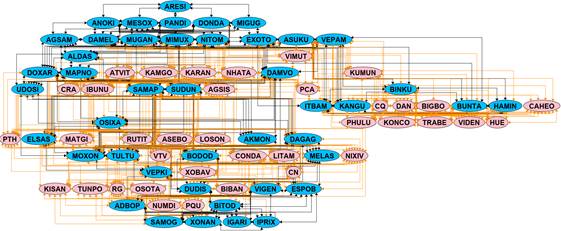

navigation. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate all node connections in the land – coast

and coast – sea regions, respectively. Land nodes are shown in green, sea nodes

in blue, and coastal nodes – appearing in both figures – are marked in pink.

Fig. 2. Connections between all nodes in the

land-coast region

Fig. 3.

Connections between all nodes in the coast-sea region

The

next crucial step in the model development is the precise definition of the

objective function, constraints, and assumptions that will be applied within

the model. This phase is fundamental, as it forms the conceptual and

mathematical backbone of the model, ensuring its effectiveness, feasibility,

and real-world applicability. Without a well-defined structure, even the most

sophisticated models may fail to produce meaningful or actionable insights. In

this model, the primary objective, across all scenarios and cases, is to

minimize the distance of the alternative route to the newly designated airport,

as specified by the user. This objective is particularly important in urban

planning, logistics, and transportation network optimization, where shorter travel

distances directly translate to lower operational costs, reduced travel time,

and improved user satisfaction. The objective function

is defined mathematically as:

![]()

where:

d is

the distance between any two consecutive nodes i

and i+1 on the ATS route that consists of u nodes.

D is

the total distance from the starting node to the ending node.

For

each ATS route, the following variables are defined:

·

![]() : A

node positioned along ATS route a between the start and end node,

defined by its latitude and longitude. Note:

: A

node positioned along ATS route a between the start and end node,

defined by its latitude and longitude. Note: ![]() ,

indicating that for each ATS route a, the node

,

indicating that for each ATS route a, the node ![]() ranges from 0 to

ranges from 0 to ![]() . Specifically:

. Specifically:

When ![]() ,

it corresponds to the starting node of ATS route

,

it corresponds to the starting node of ATS route ![]() and must coincide with the starting point of

the original route.

and must coincide with the starting point of

the original route.

When ![]() ,

it corresponds to the ending node of ATS route

,

it corresponds to the ending node of ATS route ![]() and must not coincide with the ending point of

the original ATS route. In other words, n represents the newly selected

destination airport.

and must not coincide with the ending point of

the original ATS route. In other words, n represents the newly selected

destination airport.

·

![]() ):

Indicates the latitude and longitude of the node

):

Indicates the latitude and longitude of the node ![]() .

.

·

![]() :

The length of the arc connecting node

:

The length of the arc connecting node ![]() to node

to node ![]() along ATS route

along ATS route ![]() .

.

This value is calculated using the following formula.

![]()

·

![]() :

The arc

:

The arc ![]() to

to ![]() on ATS route

on ATS route ![]() .

.

The variable ![]() is defined as a binary variable, specifically:

is defined as a binary variable, specifically:

![]()

Some

special variables related to the original ATS route t are listed as follows:

·

![]() :

represents the starting node on the ATS route t.

:

represents the starting node on the ATS route t.

·

![]() :

represents the node at position i on the ATS route t.

:

represents the node at position i on the ATS route t.

·

![]() :

represents the ending node on the ATS route t that cannot be used.

:

represents the ending node on the ATS route t that cannot be used.

·

![]() :

The area q of a polygonal area containing the original destination

airport of route t within the structured airspace

:

The area q of a polygonal area containing the original destination

airport of route t within the structured airspace ![]() ,

where aircraft operations are limited.

,

where aircraft operations are limited.

·

![]() : A

circle with radius r centered at a designated

point, contains the original destination airport of route t within the

structured airspace

: A

circle with radius r centered at a designated

point, contains the original destination airport of route t within the

structured airspace ![]() ,

where aircraft operations are limited.

,

where aircraft operations are limited.

In

this study, when the initial ATS route t encounters a No_fly_area

in the form of a circular with radius ![]() or a polygonal area

or a polygonal area ![]() ,

an alternative ATS route a must be identified to avoid these limited area and

reach a newly designated airport specified by the user (when at least one

No_fly_area contains the original destination airport). In cases where only the

node

,

an alternative ATS route a must be identified to avoid these limited area and

reach a newly designated airport specified by the user (when at least one

No_fly_area contains the original destination airport). In cases where only the

node ![]() representing

the destination airport is limited, the aircraft will be unable to use this

location.

representing

the destination airport is limited, the aircraft will be unable to use this

location.

·

Node: ∀ ![]() ∈ N,

(

∈ N,

( ![]() ,

, ![]() )

) ![]() O: In a blocked state,

O: In a blocked state, ![]() cannot establish any arcs to any other node,

where v is any node belonging to N. In this case:

cannot establish any arcs to any other node,

where v is any node belonging to N. In this case:

-

Circular area:

![]()

-

Polygon area:

![]()

In Case 1 and

Scenario 2 of Case 2, when determining an alternative route for the original

route due to a change in the destination airport, and this airport is limited

either as a single point, within a polygonal region, or within a circular area,

compliance with Equation (2) and one of the Equations (5), (6), or (7),

corresponding to the shape of the No_fly_area, must

be ensured. Additionally,

the following equation must also be satisfied.

For Scenario 1

in Case 2, in addition to satisfying Equation (2) and one of the three

Equations (5), (6), or (7) depending on the shape of the No_fly_area,

an additional objective function will be formulated. This function aims to

ensure that the alternative route changes as little as possible from the

original route while still avoiding all No_fly_area

that the original route intersected, including at least one area containing the

original destination airport.

In Scenario 3,

to ensure flexibility, users are given the option to reutilize nodes from the

original route t, excluding those located within any designated No_fly_area, to construct an alternative route a. An

additional objective function will be built:

In equations

(9) and (10), i represents the last available

node before all No_fly_area, and j represents

the first available node after all No_fly_area along

the route t.

Once the

objective functions are established, the model's fundamental constraints will

be identified and mathematically expressed as equations.

Constraint 1:

An ATS route a must establish a continuous path between the start node

and the end node, ensuring that no arcs lead into the start node or originate

from the end node. This constraint is mathematically represented by two equations.

![]()

![]()

Constraint 2:

For each intermediate node i (excluding the

start and end nodes), the number of incoming arcs must equal the number of

outgoing arcs. This flow balance condition

is represented by Equation (13).

![]()

To ensure that

the model can function effectively across all phases of ATFM while maintaining

both operational feasibility and alignment with real-world conditions, a set of

well-defined assumptions is established. These assumptions aim to balance the

model’s practical applicability with its optimization objectives, ensuring that

real-world constraints are incorporated without significantly compromising

computational efficiency or solution quality. By defining these operational

conditions in advance, the model can better accommodate the complexities of ATM

while maintaining robustness and adaptability to dynamic cases:

- Navigation Infrastructure: All navigation systems,

including Non-Directional Beacons, VHF Omnidirectional Range, and Global

Navigation Satellite Systems, are assumed to function reliably, providing

continuous and consistent coverage within designated areas. In the event of

system failures, relevant notifications will be issued, and affected nodes will

be removed from the input graph to maintain model integrity.

- Airspace Organization and Utilization: The structure

and boundaries of controlled airspace are considered static and unchanging

throughout the operational period. During pre-tactical phases, any

establishment of a No_fly_area due to military

operations or other restricted activities will be communicated in advance to

ATFM units to facilitate appropriate planning and adjustments.

- Meteorological Conditions: Adverse weather phenomena

are assumed to be forecasted accurately, allowing them to be represented as

polygons or circular areas defined by precise coordinates for integration into

the model. This ensures that weather constraints are effectively incorporated

into operational planning.

- Aircraft Operations: All aircraft are assumed to

operate under standard protocols without disruptions or priority handling due

to emergencies or unforeseen contingencies.

- The model assumes that all nodes are accessible for

the selection of alternative ATS routes, except those explicitly restricted by

predefined constraints. The connections between these nodes are established

based on geographic proximity and operational viability, ensuring that all

generated routes conform to existing airspace structures.

To ensure the

flexibility, dynamism, and adaptability of the model, No_fly_area

will be dynamically defined by inputting coordinate data based on notifications

received either during the planning phase or in real-time. Once these zones are

established, the model will identify valid nodes and permissible connections to

be incorporated into the optimization framework. This approach guarantees that

alternative routes are continuously updated in alignment with real-world

conditions while adhering to the existing airspace structure. Additionally, by

continuously adapting to evolving constraints, the system not only optimizes

operational efficiency but also upholds strict compliance with safety and

regulatory frameworks.

The

model's dynamic approach allows for the continuous optimization of alternative

routes, taking into account real-time airspace conditions, regulatory

constraints, and overall operational efficiency. By doing so, it ensures that

the designated alternative route is not only precise but also practical and

adaptable to evolving scenarios. This capability enhances the effectiveness of

ATM and route planning by minimizing disruptions, improving flight safety,

enhancing route reliability, and ensuring seamless integration with existing

airspace structures, ultimately contributing to a more resilient and efficient

aviation system. The final step of the model is to determine the heuristic

function used. In the A-star algorithm, selecting an appropriate heuristic

function is crucial, as it significantly impacts the optimization performance

of the model. This has been well-documented in previous research (Foead et al., 2025; Sathvik & Patil, 2021). The authors

conducted a comprehensive evaluation, and the results indicate that both the

Euclidean and Gaussian heuristic functions yield optimal outcomes (Nguyen et

al., 2025). However, the Euclidean function is simpler to implement. Therefore,

in this model, the Euclidean heuristic function will be adopted to enhance computational

efficiency while maintaining optimal performance.

3. RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION

To

run the model effectively, the first essential step is to identify the No_fly_area. A thorough assessment of airspace usage,

particularly for military operations, was conducted, and reports from the Civil

Aviation Authority of Vietnam regarding airports that frequently experience

flight diversions were reviewed. Based on these analyses, several

representative No_fly_areas were identified for

implementation in the model, and the results are presented in this study.

Regarding meteorological conditions, the complexity and variability of weather

patterns make it challenging to predefine specific areas for case studies

within the model. However, this limitation can be easily addressed in practical

applications, as the model is designed to automatically integrate the No_fly_area data by allowing real-time data input. As a

result, when deployed in real-world scenarios, the identification of restricted

areas due to adverse weather conditions becomes a seamless and efficient

process.

First,

the results for Case 1 are presented, in which the originally designated

arrival airport is unavailable for operations, while the surrounding airspace

remains functional. In this scenario, it is assumed that Phu Quoc International

Airport (PQU) must temporarily close due to technical equipment failure or an

aircraft incident. Consequently, Can Tho International Airport (TRN) is

designated as the alternate airport. The following two results will be

presented: The first result examines the situation where only PQU is

unavailable, affecting the establishment of ATS routes. The second result

extends the analysis by considering an additional operational issue. It assumes

that, in addition to PQU, the waypoints TATIM, and DONXO also become unusable

due to further constraints. Figure 4 illustrates the model's results regarding

the impact on initial routes across the entire ATS network due to operational

disruptions at PQU, as well as the process of inputting data for the newly

designated destination airport (referred to as new_end_node

in our model). Table 1 presents the route analysis results, including a list of

waypoints and the length of each route in the outcomes of Case 1. The analysis

indicates that two affected routes must be redirected via alternative ATS

routes to TRN. Figure 5 presents the results when only PQU is unavailable,

while Figure 6 depicts the case where PQU, TATIM, and DONXO are all

inaccessible.

Fig. 4. The route analysis results are

affected by Case 1

Tab. 1

The detailed results of the routes

include a list of waypoints and lengths in Case 1

|

|

Original route |

Alternative route

Case 1, Result 1 |

Alternative route

Case 1, Result 2 |

|

CRA – PQU |

602.243 km CRA - SOSPA - LKH - KADUM - SAPEN -

KISAN - PQU |

644.77 km CRA - SOSPA - LKH - KADUM - SAPEN -

KISAN - TRN |

644.77 km CRA - SOSPA - LKH - KADUM - SAPEN -

KISAN - TRN |

|

DAN – PQU |

885.749 km DAN - TATIM

- DADEN - MULAD - DONXO - POPET - KISAN - PQU |

928.28 km DAN - TATIM

- DADEN - MULAD - DONXO - POPET - KISAN -TRN |

941.42 km DAN - LATOM - DADEN - MULAD - KADUM

- POPET - KISAN - TRN |

Based

on the results from Figures 5, 6, and Table 1, it is evident that the model

operates accurately when identifying a new route to the newly designated

destination airport, which can be easily adjusted according to user needs. This

adaptability ensures that users can flexibly modify the destination based on

their specific needs without compromising the integrity of the routing process.

The model dynamically adjusts the path while maintaining computational

efficiency and consistency, making it highly suitable for real-world

applications. For the CRA - PQU route, the results from both runs of the model

are identical because the two waypoints, TATIM and DONXO, in the second result

do not belong to the original route. Consequently, their presence does not interfere

with the route calculation process, and the new path to the airport remains

unchanged. This highlights the robustness of the model in preserving optimal

paths when external constraints do not affect the original route structure.

However, for the DAN - PQU route, both TATIM and DONXO are integral parts of

the original route. As a result, in the second scenario, the alternative route

must also avoid these two waypoints, leading to an increase in the total travel

distance. This demonstrates the impact of waypoint constraints on the selection

of alternative ATS routes and highlights the model’s ability to navigate

complex restrictions to generate feasible and compliant alternative ATS routes.

The trade-off between distance and constraint adherence is evident in this

case, reinforcing the importance of considering waypoint dependencies in

routing optimization.

Next,

the results of the three scenarios for Case 2 are analyzed,

considering two distinct situations. Each situation involves two different No_fly_area. In the first situation, two No_fly_area are defined as polygons with the following:

(14.880556, 108.0197222), (14.479444, 107.8436111), (14.333333, 107.4000000),

(13.983333, 107.4166667), (13.957222, 109.0427778), (13.962500, 109.5213889),

(14.771389, 108.8075000) and (10.445278, 103.7763889), (10.895556,

105.2280556), (9.959444, 105.1330556), (8.500000, 104.0833333), (9.245000,

102.8383333). Upon their integration, the model identifies affected ATS routes

whose destination airports fall within these restricted zones. Notably, DAN–PQU

is impacted by both No-fly Areas, while CRA–PQU is affected by one. As a

result, rerouting to an alternate airport – assumed to be Côn

Sơn (CN) – is required. In Scenario 3, users may choose any point outside

the No-fly Area along the original route as the start_point

for diversion. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of waypoint sequences

and route lengths, followed by Figures 7-10, which depict the corresponding

adjusted routes and waypoints.

Fig. 5. Original and alternative Route

configurations when PQU becomes unavailable

Fig. 6. Original and alternative Route

configurations when PQU, TATIM,

and DONXO becomes unavailable

Tab. 2

The detailed results of the

routes include a list of waypoints and lengths in Situation 1, Case 2

|

|

Original route |

Alternative route – Scenario 1 |

Alternative route – Scenario 2 |

Alternative route – Scenario 3 |

|

CRA – PQU |

602.243 km CRA - SOSPA - LKH - KADUM - SAPEN -

KISAN - PQU |

607.569 km CRA - SOSPA - LKH - KADUM - SAPEN -

BITIS - CN |

461.276 km CRA - ELSAS - CN |

484.146 km CRA - SOSPA

- LKH - RUTIT - ELSAS – CN |

|

DAN – PQU |

885.749 km DAN - TATIM

- DADEN - MULAD - DONXO - POPET - KISAN - PQU |

1216.229 km DAN - TATIM - KUMUN - VEPAM - KAMGO

- BMT - MULAD - DONXO - POPET - BITIS - CN |

989.815 km DAN - VEPAM

- KARAN - ELSAS - CN |

1130.605 km DAN - TATIM

- KUMUN - VEPAM - KAMGO - BMT - MULAD - DONXO - ESDOB - NIXIV – CN |

Fig. 7. The route analysis results are

influenced by Situation 1 of Case 2

and the newly input destination airport data

Fig. 8: Graphical results representing the

routes of Scenario 1, Situation 1, Case 2

In

the second situation, two No_fly_area were

established: one defined as a polygon with coordinates (16.2214, 107.6013),

(16.45264, 108.89553), (15.97414, 108.7921), and (15.6712, 107.8745), and

another as a circular area centered at (16.052778,

108.1983333) with a radius of 50 km. Notably, these two restricted areas have

overlapping regions. Following a similar approach as in the first situation,

the route assessment revealed that two routes, TSH-DAN and CRA-DAN, were

initially affected by the presence of these areas. As a result, an alternative

ATS route was required, with Chu Lai Airport (CQ) designated as the new

destination. In Scenario 3, the waypoints DADEN (TSH-DAN route) and KUMUN

(CRA-DAN route) were identified as key reference points for selecting

alternative ATS routes. Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of alternative

routing solutions, including waypoint sequences and route lengths, while

Figures 11-14 illustrate the route analysis results, new airport selection,

Scenario 3 starting point, and the adjusted route visualization.

Fig. 9. Graphical results representing the

routes of Scenario 2, Situation 1, Case 2

Fig. 10. Graphical results representing the routes

of Scenario 3, Situation 1, Case 2

Tab. 3

The detailed results of the

routes include a list of waypoints and lengths in Situation 2, Case 2

|

|

Original route |

Alternative route – Scenario 1 |

Alternative route – Scenario 2 |

Alternative route – Scenario 3 |

|

TSH – DAN |

612.169 km TSH - DONXO

- MULAD - DADEN - TATIM - DAN |

579.203 km TSH - DONXO

- MULAD - DADEN - TATIM - VILOT - SADIN - CQ |

557.747 km TSH - DONXO

- MULAD - MUMGA - CQ |

565.615 km TSH - DONXO

- MULAD - DADEN - BANSU – CQ |

|

CRA – DAN |

471.176 km CRA - KARAN - KAMGO - PCA - KUMUN -

DAN |

384.668 km CRA - KARAN - KAMGO - PCA - KUMUN -

CQ |

384.668 km CRA - KARAN - KAMGO - PCA - KUMUN -

CQ |

384.668 km CRA - KARAN - KAMGO - PCA - KUMUN –

CQ |

Fig. 11. The route analysis

results are influenced by Situation 2 of Case 2

and the newly input destination airport data

Fig. 12. Graphical results

representing the routes of Scenario 1, Situation 2, Case 2

Fig. 13. Graphical results

representing the routes of Scenario 2, Situation 2, Case 2

Fig. 14. Graphical results

representing the routes of Scenario 3, Situation 2, Case 2

The

analysis of results across all cases, including Case 1, highlights the model’s

remarkable flexibility and adaptability in selecting any airport as an

alternative destination. Regardless of the chosen replacement airport, the

model consistently generates accurate solutions that align with predefined

objective functions, ensuring operational feasibility and efficiency. This

adaptability is a key indicator of the model’s robustness, demonstrating its

capability to handle a wide range of operational constraints in dynamic ATM

environments.

A

more in-depth examination of the results in the two situations of Case 2

further confirms this observation. In both situations, all designed scenarios

are effectively fulfilled. Specifically, in Scenario 1, the alternative ATS

route closely follows the original ATS route, except for segments that require

modifications to bypass the No_fly_area, as well as

final adjustments necessary to reach the newly designated destination airport.

In Scenario 2, the selected ATS route consistently represents the shortest

among all feasible alternatives, confirming the model’s ability to identify

efficient alternative ATS routes. In Scenario 3, the model exhibits a high

degree of flexibility by dynamically determining the alternative ATS route

based on a user-specified start_point.

A

particularly noteworthy observation emerged in the case of the CRA–DAN route,

where the alternative ATS routes remained identical across all three scenarios.

This outcome can be attributed to the fact that No_fly_area

did not affect the initial segments of the original route. As a result, these

segments naturally formed the shortest possible path to the destination,

requiring no further optimization. This insight suggests that, in certain

cases, pre-existing route structures inherently align with optimal alternative

ATS route planning, thereby reducing the need for significant deviations.

Moreover,

the results obtained from Situation 1 and Situation 2 collectively reinforce

the model’s independence from the shape, size, and distribution of the No_Fly_area. Whether these areas are separate or

overlapping, the model consistently identifies the most suitable alternative

ATS route while ensuring compliance with airspace regulations. This

adaptability is crucial in complex airspace environments where restricted areas

may change dynamically due to geopolitical constraints, military operations, or

emergency airspace closures.

The

simulation results indicate that the model not only successfully identifies

alternative ATS routes but also ensures that these routes are operationally

feasible and compatible with all phases of ATFM. This is particularly critical

when one or more No_fly_area emerge due to both

unforeseen circumstances, such as adverse weather conditions, security threats,

or emergencies, and pre-planned situations, such as military exercises or

special airspace restrictions. These disruptions can significantly impact airport

operations and necessitate rapid aircraft diversions. Furthermore, the model

can be applied across different ATFM phases, particularly during the

pre-tactical stage, where planning and foresight are prioritized, and the

tactical stage, where flexibility and real-time adaptability are crucial for

responding to evolving situations. This capability is especially valuable in

high-traffic airspace environments, where maintaining efficiency and safety is

paramount. A key strength of the model lies in its high adaptability and

ability to dynamically optimize flight routes to accommodate operational

constraints. This demonstrates its practical applicability in ATM and

decision-making processes, contributing to enhanced efficiency, safety, and

resilience in airspace operations. In addition to enhancing the efficiency and

reliability of air traffic flows, the model contributes to reducing fuel

consumption and emissions by minimizing unnecessary detours and delays. This

aligns with broader goals of sustainable aviation and environmental

responsibility, further emphasizing its significance in modern ATM and

operational planning.

Overall,

the results confirm that the model performs reliably in alternative ATS routing

scenarios, demonstrating its effectiveness in addressing complex route planning

challenges. Its ability to adapt to changes while maintaining route

feasibility and efficiency makes it a powerful tool for applications requiring

dynamic navigation and optimized pathfinding under varying constraints.

4. CONCLUSION

Beyond

serving as a dynamic decision-support tool for identifying alternative ATS

routes when aircraft must divert to an alternate destination, this framework

can be effectively applied to a variety of operational scenarios, significantly

enhancing ATM efficiency and resilience. One of its key applications is the

development of contingency flight paths tailored to specific airspace regions

prone to frequent disruptions due to adverse weather conditions, high traffic

density, or unforeseen technical issues. By preemptively

designing such backup routes, air navigation service providers (ANSPs) can

ensure seamless operational continuity, minimizing delays and optimizing

airspace utilization under challenging circumstances. Furthermore, this model

can play a crucial role in enhancing trajectory-based operations (TBO) by

accurately determining real-time flight paths during various phases of

operation.

Importantly,

the implementation of alternative routing solutions in this model does not

require fundamental changes to existing airspace structures or control sectors.

Instead, it strategically utilizes current navigation aids, waypoints, and

predefined air traffic corridors, enabling a seamless integration within

existing ATM frameworks. This minimizes the need for costly infrastructural

overhauls while maximizing the effectiveness of available airspace resources.

This approach enhances flexibility and responsiveness while preserving the

integrity of established airspace management systems. By adopting this model,

ATC can proactively implement strategic decongestion measures, mitigating

bottlenecks and optimizing sector workload distribution while adhering to

established ATFM protocols. Moreover, the model enhances the capacity to

provide real-time guidance in response to unforeseen situations, ensuring

operational resilience. This adaptability is particularly valuable in

high-density airspace, where the ability to swiftly reassign flight paths

contributes to both safety and efficiency.

One

significant advantage of this model is its adaptability to various airspace

structures, achieved simply by modifying the input data, which consists of a

list of waypoint coordinates and airports within the designated airspace. This

flexibility allows for seamless integration into different ATM systems,

optimizing navigation efficiency across diverse operational environments. This

capability of the model ensures its applicability across a wide range of

scenarios, from managing low-density regional airspaces to handling

high-traffic international corridors. By dynamically adjusting to varying

airspace configurations, the model enhances route planning, minimizes

congestion, and contributes to the overall safety and efficiency of ATM.

Ultimately,

this approach significantly strengthens flight safety, enhances operational

predictability, and improves the adaptability of ATM systems without

necessitating structural changes to the FIR. By integrating such a framework,

ANSPs can modernize ATM operations, improve airspace utilization, and better

align with next-generation aviation initiatives. By leveraging these

advancements, the aviation industry can move toward a more intelligent ATM

model that ensures greater flexibility, dynamism, and adaptability in all

operational scenarios. This transformation is particularly crucial in an era of

increasing air traffic demand, evolving regulatory frameworks, and the

integration of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence,

automation, and unmanned aerial systems.

References

1.

6Wresearch. 2024. "Vietnam aviation market

(2023-2029) outlook". Available at: https://www.6wresearch.com/industry-report/vietnam-aviation-market-outlook.

2.

Beeker E. 2004. "Potential error in the

reuse of Nilsson’s A algorithm for path-finding in military simulations". Journal

of Defense Modeling and Simulation 1(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/875647930400100203.

3.

Bongo M.F., C.L. Sy. 2020. "A robust optimisation formulation for post-departure rerouting

problem". In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on

Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management: 509-513. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM45057.2020.9309827.

4.

Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 2025.

"On-time performance – Reporting operating carrier flight delays at a

glance". Available at: https://www.transtats.bts.gov/homedrillchart.asp.

5.

Carreras R., C. Greenman. 2025. "Vietnam’s

vision of growth in the aeronautical industry". Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/publication/740.

6.

Eurocontrol. 2024. "Cost of

diversion". Available at: https://ansperformance.eu/economics/cba/standard-inputs/chapters/cost_of_diversion.html#eurocontrol-recommended-values.

7.

Federal Aviation Administration. 2025.

"Airport benefit-cost analysis guidance". Available at: https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/regulations_policies/policy_guidance/benefit_cost/FAA_Airport_Benefits_Guidance.pdf.

8.

Felix Y.W., H.L.H.S. Warnars,

L.L.H.S. Warnars, A. Ramadhan, T. Siswanto. 2024.

"Searching routing using A-Star (A*) search algorithm". In: Proceedings

of the 3rd International Conference on Creative Communication and Innovative

Technology (ICCIT): 1-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCIT62134.2024.10701177.

9.

Foead

D., A. Ghifari, B.M. Kusuma, N. Hanafiah, E. Gunawan.

2021. "A systematic literature review of A* pathfinding". Procedia

Computer Science 179: 507-514. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.034.

10. International

Trade Administration. 2024. "Aviation: Country commercial guide –

Vietnam". Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/vietnam-aviation.

11. Ji

Y., X. Wu, Y. Shang, H. Fu, J. Yang, W. Wu. 2024. "Unmanned ground vehicle

in unstructured environments applying improved A-star algorithm". In: Proceedings

of the 4th International Conference on Computer, Control and Robotics (ICCCR):

166-170. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCR61138.2024.10585482.

12. Ju

C., Q. Luo, X. Yan. 2020. "Path planning using an improved A-star

algorithm". In: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on

Prognostics and System Health Management (PHM): 23-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/PHM-Jinan48558.2020.00012.

13. Kabir

R., Y. Watanobe, M.R. Islam, K. Naruse. 2024.

"Enhanced robot motion block of A-star algorithm for robotic path

planning". Sensors 24(5): 1422. ISSN: 1424-8220. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/s24051422.

14. Kurniawan

R., A. Armansyah, M. Idris. 2024. "Application

of artificial intelligence in the design of 2D Escape From Pirates game with A

Star algorithm search method". Jurnal

Dinda: Data Science, Information Technology, and Data Analysis 4(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.20895/dinda.v4i2.1558.

15. Li

J., C. Yu, Z. Zhang, Z. Sheng, Z. Yan, X. Wu, W. Zhou, Y. Xie, J. Huang. 2023.

"Improved A-star path planning algorithm in obstacle avoidance for the

fixed-wing aircraft". Electronics 12(24): 5047. ISSN: 2079-9292.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12245047.

16. Ma

L., H. Zhang, S. Meng, J. Liu. 2022. "Volcanic ash region path planning

based on improved A-star algorithm". Journal of Advanced Transportation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9938975.

17. Mandloi D., R. Arya,

A.K. Verma. 2021. "Unmanned aerial vehicle path planning based on A*

algorithm and its variants in 3D environment". International Journal of

System Assurance Engineering and Management 12: 990-1000. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-021-01186-9.

18. Neretin E.S., A.S. Budkov,

A.S. Ivanov. 2021. "Optimal four-dimensional route searching methodology

for civil aircrafts". In: Li B., C. Li, M. Yang, Z. Yan, J. Zheng (Eds.). IoT

as a Service 346: 433-442. Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67514-1_37.

19. Nguyen

Ngoc Hoang Quan, V.N. Nechaev, V.B. Malygin. 2025.

"Mathematical model and application of the A-star algorithm to optimize

ATS routes in the Area Control Center Ho Chi Minh airspace". Crede Experto: Transport, Society, Education, Language 1: 64-78.

ISSN: 2312-1327. DOI: https://doi.org/10.51955/2312-1327_2025_1_64.

20. OAG

Aviation Worldwide Limited. 2024. "The busiest flight routes of

2024". Available at: https://www.oag.com/busiest-routes-world-2024.

21. Roy

K.R. 2023. "Obstacle avoidance for quadcopters in formation flying based

on A* algorithm". In: Jain K., V. Mishra, B. Pradhan (Eds.). UASG 2021:

Wings 4 Sustainability 304: 443-456. Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19309-5_34.

22. Sathvik

N.G., S. Patil. 2021. "Performance analysis of Dijkstra’s and the A-star

algorithm on an obstacle map". In: Bhateja V., S.C. Satapathy, C.M. Travieso-González,

V.N.M. Aradhya (Eds.). Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing

1407: 81-90. Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0171-2_8.

23. VietnamPlus. 2025.

"Flights diverted, delayed due to bad weather at Tan Son Nhat

airport". Available at: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/flights-diverted-delayed-due-to-bad-weather-at-tan-son-nhat-airport-post253559.vnp.

24. Wang

Y., L. Qian, M. Hong, Y. Luo, D. Li. 2024. "Multi-objective route planning

model for ocean-going ships based on bidirectional A-star algorithm considering

meteorological risk and IMO guidelines". Applied Sciences 14(17):

8029. ISSN: 2076-3417. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/app14178029.

25. Xu

Y., R. Dalmau, M. Melgosa, A. Montlaur, X. Prats. 2020.

"A framework for collaborative air traffic flow management minimizing

costs for airspace users: Enabling trajectory options and flexible pre-tactical

delay management". Transportation Research Part B: Methodological

134: 229-255. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2020.02.012.

26. Yang

S., n Y. Ya, P. Chen. 2021. "Robust optimization models for flight

rerouting". International Journal of Computational Methods 18(5).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219876220400010.

Received 25.07.2025; accepted in revised form 30.10.2025

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License