Article

citation information:

Melnyk,

O., Onyshchenko, S., Zhykharieva,

V., Pavlova, N., Volianska, Y., Andriievska,

V., Korobkova, O. Analytical model for ship grace-period optimization via a single window

platform: a Tianjin port case study. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2025, 129, 147-168. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2025.129.9

Oleksiy MELNYK[1],

Svitlana ONYSHCHENKO[2], Vlada ZHYKHARIEVA[3], Nataliia PAVLOVA4, Yana VOLIANSKA5, Vira

ANDRIIEVSKA6, Olena KOROBKOVA7

ANALYTICAL MODEL

FOR SHIP GRACE-PERIOD OPTIMIZATION VIA A SINGLE WINDOW PLATFORM: A TIANJIN PORT

CASE STUDY

Summary. The article presents an

analytical model for optimizing the "grace period" of mooring and

documentary clearance of ships in the port of Tianjin by introducing a

centralized "single window" platform. The functional roles of the key

documents - Forwarder's Cargo Receipt (FCR) and Shipping Order - regulating the

readiness of cargo for loading and confirming the completion of customs

clearance are investigated. Based on regulatory analysis, expert interviews,

and simulation modeling, critical bottlenecks in the

processes of verification and berth slot assignment are identified. A

stochastic model of the total processing time was developed, where each stage

is described as an independent, normally distributed random variable. Using

this model, the probability of exceeding the permissible processing interval is

estimated, and the feasibility of automating document flow is substantiated.

Technical and organizational solutions for implementing a unified digital

infrastructure, including standardized exchange formats, double data

validation, electronic stamping, and integration with PCS/TOS, are proposed.

This creates the basis for utilizing these results in the development of

intelligent port systems and enhancing the efficiency of logistics operations.

Keywords: port operations, project optimization, maritime logistics, berth

assignment, management system, shipping, documentation flow, freight

forwarding, cargo handling, shipping order, customs clearance, transportation

process, port community systems, stochastic process simulation, terminal

operating systems, operational efficiency, stakeholder coordination

1.

INTRODUCTION

The Port of Tianjin is

one of the largest transshipment hubs in Northern China, with millions of tons

of cargo passing through it annually. Ensuring timely delivery and mooring of

vessels in the port depends on the clarity of documentary procedures and operational

interaction between shippers, freight forwarders, customs, terminals and ship

agents. Particularly important are the FCR (Forwarders Certificate of Receipt)

and Shipping Order documents, which determine the readiness of the cargo for

loading and the port's ability to assign a berth to the vessel. In today's

environment of growing security boundaries, digitalization of the supply chain,

and increased customer expectations, improving these procedures is key to

increasing the efficiency and reliability of port operations.

The modern scientific

literature addresses the issues of digitalization and optimization of port

operations in several interrelated areas. Thus, the digital transformation in

maritime logistics is studied in the work of Zeng et al. (2025), who conducted a

systematic review of the drivers and obstacles to digitalization in maritime

logistics, finding that there is a lack of common data exchange standards and

an adequate level of digital literacy among employees. Fruth & Teuteberg

(2017) emphasize the gaps in the integration of information systems between

chain actors, while Jović et al. (2024) use the example of Croatia to

demonstrate how digital transformation increases process transparency and

reduces cargo handling time.

Blockchain and secure

document exchange have been studied by Liu (2021) and Alahmadi et al. (2022)

comparing blockchain-based platforms for the exchange of cargo documents,

proving the benefits of a distributed ledger in reducing the risk of forgery.

Chang et al. (2019), Jovanović et al. (2022), Yang (2019), and Guan et al.

(2024) summarize the possibilities of blockchain in global supply chains, while

Ni & Irannezhad (2023), Shin et al. (2023), and

Karakaş et al. (2021) emphasize its role in port ecosystem management.

Information systems

and terminal automation are presented by González-Cancelas et al. (2020) and

Camarero Orive et al. (2020) who apply SWOT analysis to assess the

digitalization and automation of container terminals in Spain. Heilig & Voß (2017) categorize information systems in ports, and Lee

et al. (2018) propose a DSS for making ship speed decisions based on large

amounts of weather data.

Decision support and

simulation in Lee et al. (2018), where the authors developed a decision support

system for optimizing ship speed using archived meteorological data, and Wang

et al. (2024) simulate the traffic of ultra-large ships in the port of Ningbo

Zhoushan, providing important insights for berth slot management.

Prediction of cargo

flows and downtime has been studied by Patil & Sahu (2016), Al-Deek (2001) and Munim et al. (2023) where they compare

regression, time series, and hybrid models to forecast container flows in key

Asian ports. Yu et al. (2025) combine graph theory and time series for a

detailed traffic forecast, while Morales-Ramírez et al. (2025) use

autoregressive models to analyze national freight

traffic. Chu et al. (2025) and Pham & Nguyen (2025) apply ensemble

approaches and machine learning to ship arrival time forecasting, and Huang et

al. (2024) apply them to terminal energy requirements. Das & Saxena (2025),

Osadume et al. (2025), Abd Rahim et al. (2024), Nwoloziri et al. (2025), and Cuong et al. (2022) study the

impact of the COVID-19 crisis on cargo flows, downtime costs, and port

recovery.

The economic impact of

the crisis is assessed in Das & Saxena (2025), which analyzes

the impact of the pandemic on freight and revenues in India, Osadume et al. (2025) on the operation of Nigerian ports,

and Nwoloziri et al. (2025) on the costs of delays in

Apapa ports. Models of risk and safety of ship operations were analyzed by Guo et al. (2024) developed an optimal

emergency resource allocation model with multi-criteria optimization, and

Darwich & Bakonyi (2025) investigated the development of port infrastructure

in East Africa. Gondia et al. (2023) apply ML methods

for dynamic risk assessment in construction, Nagurney et al. (2024) -

integrated insurance for operations during military conflicts. Melnyk et al.

(2024, 2025) serially develop concepts for the safety of cargo operations, analysis

of the structural reliability of navigation systems, and cluster analysis of

incidents. Kobets et al. (2023), Zinchenko et al. (2023, 2024) propose

automated algorithms for positioning, collision avoidance, and parametric

rolling, while Melnyk et al. (2023) evaluate the effectiveness of expert risk

management methods.

Specialized studies of

port management have been carried out by Abd Rahim et al. (2024), who studied

the impact of air pollution on the health of workers in the Klang port area.

Guo et al. (2025) forecasted water needs for irrigation of oil ports, Luidmyla et al. (2025) proposed a new approach to modeling the unloading process, Varbanets

et al. (2024) – who designed diagnostics of diesel engines of marine vessels; Zhikharieva (2025) – benchmarking of intangible assets of

shipping, and Nikolaieva et al. (2025) formalized

hybrid models of terminal management based on KPIs.

Despite a wide range

of studies on the digitalization of port processes, blockchain solutions, and

information systems in terminals, the integration of key FCR and Shipping Order

documents into a single electronic window remains underestimated in current

practice. The absence of such a solution in ports can lead to significant

delays at the stages of customs clearance and mooring assignment for ships.

Problem statement. Despite the important role of the FCR as the primary confirmation of

cargo acceptance by the forwarding agent, this document does not certify the

fact of customs clearance and readiness of the cargo for loading onto the

vessel. At Tianjin port terminals, the FCR alone does not provide a basis

for mooring slot assignment: without a stamped Shipping Order, the port cannot

verify that the cargo has cleared all customs formalities and is located in the

proper place in the terminal.

Consequently, freight

forwarders and shipowners encounter delays in the mooring process, extending

the “grace period” and resulting in additional financial costs. The lack of an

integrated data exchange system between freight forwarders, customs, the port

authority, and ship agents causes bottlenecks that have a negative impact on

port throughput and reduce the overall efficiency of the supply chain.

Purpose and objectives of the study. The purpose of this study is to analyze

the existing workflow and procedures of port operations in Tianjin, identify

bottlenecks related to the use of FCR and Shipping Order, and propose practical

digital solutions to improve them.

Objectives:

-

describe the

regulatory framework and the role of the FCR and Shipping Order in the port of

Tianjin;

-

identify the key

points of delay in the customs clearance procedure and ship mooring assignment;

-

analyze the experience of

terminals in checking the status of cargo in the port's internal systems;

-

develop

recommendations for implementing a single electronic window and automating

document exchange;

-

estimate the expected

economic effect of reducing downtime and optimizing the grace period.

The scientific novelty

of the article lies in the combination of probabilistic modeling

of the total vessel downtime (with the distribution of the constituent stages

of the document flow: FCR, customs clearance, verification, slot assignment)

with the economic function of downtime costs and the concept of implementing a

"single electronic window" for the automated exchange of FCR and

Shipping Order. For the first time, an analytical model of exceeding the

"grace period". Based on real data from the Tianjin Port, it is

proved that digital integration of document flow can provide annual savings and

increase port throughput.

2. METHODOLOGY

This study uses a combined approach that

combines qualitative and quantitative methods to comprehensively examine the

document flow process at the Port of Tianjin. First, a detailed analysis of the

regulatory framework was conducted: official instructions of the Administration

of Customs of the People's Republic of China and the Tianjin Terminal Rules

were studied, and a comparative analysis of the internal procedure cards

Forwarders Certificate of Receipt (FCR) and Shipping Order was performed. It is

important that one of the authors has more than many years of experience in

Chinese ports, including the port of Tianjin as a representative of an

international shipping company, which also allowed the authors to take into

account the practical nuances and internal logistics of port procedures and to

reproduce the formal requirements for the content and sequence of these two key

documents.

Secondly, semi-structured interviews with port

industry practitioners were organized to identify the actual processing times

and reasons for delays: interviews were conducted with three ship agents, two

representatives of forwarding companies, and a terminal operator. The

interviews provided empirical data on the time intervals between the issuance

of the FCR, the customs stamping of the Shipping Order, and the mooring slot

assignment.

And thirdly, to assess the existing IT

infrastructure of the port, a review of the Shipping Order acceptance module in

the Port Community System (PCS) was carried out. The user interface, business

logic of document processing, and data exchange mechanisms between PCS, the

customs system, and ship agents were analyzed.

Finally, in the quantitative part of the study,

a statistical analysis of ship calls during 2022-25 was performed. Based on the

collected data, the average time from the issuance of the FCR to the affixing

of the Shipping Order customs stamp, as well as the time until the actual

mooring slot is assigned, was estimated. The obtained numerical characteristics

formed the basis for further development of the analytical model and assessment

of economic losses due to delays.

3. RESULTS

The

regulatory framework and the role of FCR and Shipping Order in the port of

Tianjin

Before moving on to describe specific

procedures, it is important to outline the legal framework in which the

document flow in the port of Tianjin operates. A combination of national laws,

municipal regulations, and international guidelines forms a two-stage cargo

verification mechanism: first, the freight forwarder confirms the fact of

acceptance, and then the customs and terminal confirm the cargo's readiness for

operations.

The regulation of document flow in the port of

Tianjin is based on both general Chinese legislation and special rules of the

port administration and customs authorities. Key regulatory sources include:

1. The

Law of the People's Republic of China "On Customs Control" and bylaws

that establish requirements for the execution of cargo documents, the procedure

for their submission to the customs authorities, and the procedure for affixing

customs stamps. These provisions stipulate that only a document with a customs

stamp (Shipping Order) is recognized as an official confirmation of the

completion of the customs clearance procedures and the readiness of the cargo

for unloading or loading onto a vessel.

2. The

Tianjin Port Administration Rules approved by the Tianjin Municipal Port

Administration, which regulate the procedures for mooring assignment, berth

management, and interaction between the port authorities, terminals, ship

agents, and freight forwarders. According to these rules, terminals are obliged

to check the availability of a Shipping Order before issuing berthing

instructions.

3. The

harmonized rules of the International Federation of Freight Forwarders (FIATA)

on Forwarders Certificate of Receipt (FCR), which globally recognize the FCR as

an internal document of the forwarder to confirm the acceptance of cargo.

However, in China, the FCR, although compliant with the FIATA international

standard, is used primarily to register the fact of acceptance of cargo from

the sender but is not a basis for customs clearance or mooring assignment

(Table 1).

Tab. 1

Key regulatory sources

and their requirements

|

Regulatory

source |

Main provisions |

|

Customs Law of People’s

Republic of China |

- requirements for cargo documents; - the customs stamp on the Shipping Order is the

only proof of customs clearance and readiness for loading. |

|

Tianjin Port Administration Rules |

- list of documents for mooring assignment; - mandatory check of the Shipping Order before

issuing mooring instructions. |

|

FIATA recommendations

on FCR |

- FCR is recognized as an international standard for

confirming the acceptance of cargo by the forwarder; - in China, the FCR does not replace the Shipping

Order during processing at the port. |

Study of the role of both documents in the process

The Forwarder's Certificate of Receipt (FCR) is

a key document that serves as an internal confirmation of cargo acceptance by

the forwarder. Its main role is to record the fact of cargo transfer,

accompanied by a detailed description: the name of the sender, the number of

pieces, the nature of the cargo, the port of destination, and other mandatory

details. All this data must fully comply with the future Shipping Order

submitted to the customs authorities.

In practice, the FCR serves as the basis for the

formation of the Shipping Order: the freight forwarder uses the information

from the FCR to prepare a draft document, which is then sent for approval and

stamping by the customs. Thus, the FCR performs not only a confirmatory but

also a translational function in the customs clearance procedure, reflecting

internal control at the stage of cargo acceptance.

Table 2 shows the main tasks performed by FCR in

the process of organizing port logistics.

Tab. 2

Main tasks performed by FCR

|

Function |

Description |

|

Confirmation of

cargo acceptance |

The name of the sender, description, quantity, and

port of destination are the same details as in the Shipping Order |

|

The basis for the formation of the Shipping Order |

Based on the FCR data, the forwarder initiates

customs clearance and automatically transfers these details to the Shipping

Order project |

The role of Shipping Order in the port procedures

Shipping Order is a central document in the

system of port clearance and interaction between participants in the logistics

process. Its functional importance is as follows:

- confirmation of

customs clearance: the customs stamp on the Shipping Order certifies that the

cargo has been officially cleared and allowed for loading or unloading. This is

the only document that has legal force in confirming the completion of all customs

formalities;

- basis for planning

port operations: in the port of Tianjin, the Shipping Order is a mandatory

document for setting the time and place for mooring a vessel. Terminal

operators use it to reserve a mooring slot, which helps to avoid delays and

optimize cargo turnover;

- communication

interface: through integration with the Port Community System (PCS), the

Shipping Order is automatically sent to customs, port authorities, ship's agent

and other responsible services. This ensures the coordinated work of all

parties – from the moment the cargo arrives to the moment the vessel is

actually moored.

Thus, the Shipping Order not only formalizes the

fact of customs clearance and serves as a logistics coordinator and a digital

marker of cargo readiness for processing. Its functions are systematized in

Table 3.

Tab. 3

Main functions and designation of Shipping Order

|

Function |

Description |

|

Proof of customs

clearance |

The electronic or paper stamp of the customs office

on the Shipping Order confirms that the cargo has passed all the formalities |

|

Reasons for

mooring arrangements |

Only after successful verification of the Shipping

Order, the terminal operator reserves a berth slot and schedules maintenance |

|

Communication bridge via PCS |

The Shipping Order is sent out automatically through

the Port Community System, informing customs, the terminal and the ship's

agent about the readiness of the cargo |

Upon analyzing the

regulatory framework and the respective roles of the two documents, it becomes

clear that, while the FCR is responsible for the initial confirmation of

acceptance, it cannot form the basis for any port operations without a customs

clearance stamp. Conversely, the Shipping Order bearing

a customs stamp carries legal force for transporters and is a technical

necessity for port services. This two-step process strikes a balance

between the speed of document processing and strict compliance with Chinese

customs and legal requirements.

Thus, the combination of international FIATA

(FCR) recommendations and Chinese national requirements for the Shipping Order

creates a two-stage cargo control mechanism: the first stage confirms

acceptance, and the second stage ensures readiness for operations in the port.

This strikes a balance between the efficiency of document flow and compliance

with Chinese customs and legal requirements.

Key points of delay in the customs clearance procedure and the mooring

assignment

The main bottlenecks in the procedure of

paperwork and processing of documents that lead to delays in ship calls at the

Port of Tianjin can be grouped as follows:

1. Reconciliation

and verification of details between the FCR and the draft Shipping Order often

require additional time: if the data on the port of destination, cargo name, or

shipper does not match, the forwarder has to correct errors and resubmit the

application through the Port Community System, which adds an average of 1-2

hours of downtime.

2. Waiting

for the customs stamp is the longest stage: the customs officer checks not only

the documents but also the physical condition of the cargo, if necessary, and

then affixes the stamp. At peak times, this procedure takes an average of 4-6

hours and can extend up to 8 hours.

3. Technical

failures in the exchange of XML-packages between the customs and port systems

are likely to lead to "hangs" or format errors (duplicate files,

incorrect encoding), which makes information about the stamped Shipping Order

unavailable to the terminal for an additional 1-2 hours.

4. Upon

receipt at PCS, the Shipping Order must be manually verified by the berth

department operator: all cargo data must be checked against the terminal's

internal database (including the location of containers), which usually takes

another 1-2 hours.

Finally, only after successful verification of

the Shipping Order, the port administration generates a berth slot (lineup

instruction). During normal business hours, this process takes up to 1 hour,

while during night shifts and weekends it can take up to 3 hours. Taken

together, all these stages form a total "grace period" of 8-12 hours,

which often exceeds the regulatory limits and causes significant financial

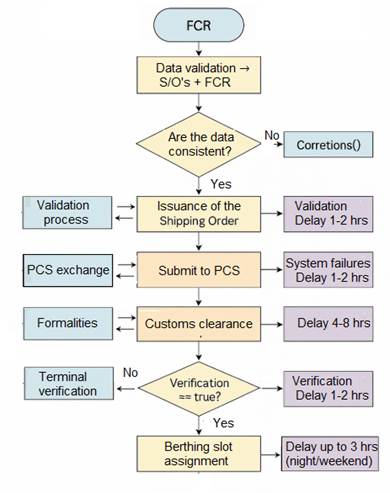

losses due to the ship’s idle condition (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Document processing

algorithm and berth slot assignment

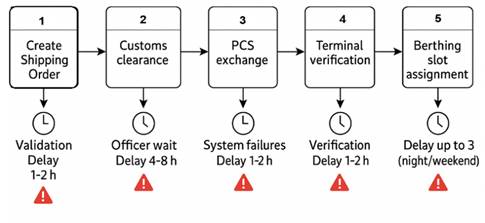

The diagram in Figure 2 shows the step-by-step

process of Shipping Order issuance and berth slot assignment, with key points

of delay at each stage highlighted. Each block indicates the main action and

sequence of operations, and below them are possible delays (hours) with the

corresponding warning icons.

The diagram shows that the largest downtime is

during customs clearance (4-8 hours) and initial data verification (1-2 hours

for each of several steps). Smaller delays (1-2 hours) are caused by system

checks and data exchange in PCS, and during non-operational hours, an

additional 1-3 hours when assigning a berth slot. These bottlenecks should be

optimized by automating validation, increasing the throughput of exchange

systems, and introducing flexible slots to accommodate night and weekend

shifts.

Fig. 2. Shipping Order processing process with key

points of delay

As a result, it takes an average of 8-12 hours

from the general moment of issuing the FCR to receiving the mooring

instruction; on peak days, this interval can reach 14-16 hours, which

significantly exceeds the optimal "grace period" and leads to

additional costs due to vessel downtime.

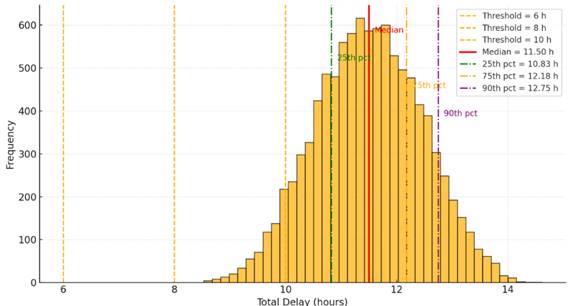

Additionally, a stochastic modeling

of the total delay of the procedure "FCR - SO - PCS - customs clearance -

mooring" was carried out. The Monte Carlo method with 10,000 iterations

was used, in which delays at each of the five stages were generated according

to uniform distributions (1-2 hours, 4-6 hours, 1-2 hours, 1-2 hours, 1-3

hours, respectively). The resulting distribution of total time allows us to

estimate the key statistical characteristics of the process and the probability

of exceeding critical time thresholds, Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Distribution of the total process delay

(histogram) with thresholds of 6 hours, 8 hours, 10 hours, as well as the

median (50%), 25%, 75%, and 90% quantiles

The range of results clearly shows that the

median total delay is approximately 11.5 hours, the 25th percentile is 10.8

hours, the 75th percentile is 12.2 hours, and the 90th percentile is 12.8

hours. Thus, the probability of exceeding the 10-hour limit reaches about 94%,

which indicates a high risk of delays beyond this threshold. The less critical

thresholds of 6 and 8 hours are almost always exceeded (with a probability of

approximately 100%), which requires optimization of key process steps to reduce

downtime and increase the efficiency of the supply chain.

Experience of terminals in checking cargo status in the port information

system

After the Shipping Order is created and stamped

by customs, an email is instantly generated in PCS and sent to the

corresponding Terminal Operating System (TOS) module of the terminal. In TOS,

the cargo receives the "Cleared" status, which makes it available for

further mooring planning. The terminal operator views the Shipping Order data,

the actual location of the container through the WMS, and additional parameters

(weight, radiological checks) in a single interface. If any field does not match,

the system displays a "yellow" warning status and blocks automatic

slot generation.

Once the Shipping Order is in the

"Cleared" status, the TOS automatically sends SMS and e-mail

notifications to the ship's agent and freight forwarder. Although the formal

SLA for status confirmation is 30 minutes, during peak periods this step takes

about 45-60 minutes. For exceptional situations when the application hangs due

to XML errors or API timeouts (1-2% of cases), operators use the manual tool

"Force Clear" after visually checking the original document.

Every day, TOS generates a report on key

metrics: the average time from "Cleared" to the issuance of a

berthing instruction (≈ 1 hour) and the share of Shipping Orders with

delays of more than 2 hours (less than 3% of cases). These indicators are analyzed weekly by the port's customer service to identify

trends and eliminate bottlenecks.

In Figure 4 shown a generalized

sequence-diagram, illustrating the main data flow between the forwarding agent,

Port Community System (PCS), Customs, and Terminal Operating System (TOS).

The diagram illustrates the sequence of digital

processing in the Port Community System (PCS), where the agent sends the FCR

and Shipping Order, the PCS requests electronic approval from customs, and then

receives back the confirmed document with a stamp. PCS then informs the TOS

system that the cargo is ready, and TOS, in turn, sends instructions for

mooring the vessel.

Field interviews and a detailed review of

internal procedures revealed that each terminal at the Port of Tianjin uses its

own Terminal Operating System (TOS) module, integrated with the port-wide Port

Community System (PCS). This combination allows for near-instant data exchange

and automation of key steps, but also reveals technical bottlenecks that need

to be addressed when optimizing processes, Table 4.

Fig. 4. FCR and Shipping Order processing in the Port

Community System (PCS)

Tab. 4

Main stages and mechanisms for checking the

status of cargo in PCS & TOS

|

№ |

Stage / Functional unit |

Description of the

operation and key indicators |

|

1 |

PCS - TOS integration |

- after the Shipping Order is stamped in PCS, a

notification is automatically sent to the terminal's TOS; - the "Cleared" status means that the

cargo and the vessel are ready for mooring. |

|

2 |

Multimodal verification |

- the TOS interface contains Shipping Order data,

container location (WMS), and the results of additional checks; - a "yellow" warning status in case of

discrepancies blocks further processing. |

|

3 |

Automated notifications and SLAs |

- SMS/email notification to the agent and forwarder

when the status is "Cleared"; - the target SLA is 30 minutes; in fact, 45-60

minutes during peak hours. |

|

4 |

Handling of exceptional situations |

- 1-2% of applications hang due to XML errors/API

timeouts; - Force Clear tool for emergency status assignment

after visual inspection. |

|

5 |

Analytics and reporting |

- daily report: time from "Cleared" to

"Berth Instruction" (≈ 1 hour), share of delays > 2 hours

(< 3%); - weekly trend analysis by the customer service to

identify and eliminate bottlenecks. |

Thus, the deep integration of PCS with TOS

allows terminals to quickly confirm the readiness of cargo, minimize human

errors, and reduce delays. At the same time, the Force Clear mechanism and

daily monitoring of key indicators ensure the stability of the process even in

the event of technical failures.

Recommendations

for the implementation of a single electronic window and automated document

exchange

To improve the document flow process, in this

case using the example of the port of Tianjin, several interrelated measures

were introduced aimed at eliminating critical bottlenecks related to the use of

FCR and Shipping Order. These measures address the technological, procedural,

and organizational aspects of creating a digital environment designed to reduce

processing time, increase transparency, and minimize human involvement in

operations.

The first step is to create a centralized Single

Window platform that will bring together all the key parties in the chain -

freight forwarders, customs, terminal operators and ship agents - in a single

digital system. This will simplify the submission of documents and reduce the

number of duplications. At the same time, standardized data formats (XML/JSON)

that comply with international protocols should be introduced using a secure

transmission channel.

An important step is the automatic creation of

Shipping Orders based on FCRs, which reduces the time for verification and

minimizes errors. Customs electronic stamping is integrated into the same

digital space, providing a transparent and consistent approval procedure. The

system must support automatic notifications and SLA compliance monitoring,

which allows for avoiding delays and responding promptly to deviations. It is

also planned to implement double data validation, both hard and soft, with

prompts for correcting errors before submission.

Ultimately, all transactions should be

documented in a secure distributed ledger to guarantee audit transparency. The

implementation occurs gradually, accompanied by compulsory staff training. The

overall framework of these steps is outlined in the table below, Table 5.

Each of the above measures is aimed at improving

a specific node of interaction between the participants in the supply chain.

For example, a centralized platform provides a single sign-on, while automatic

document generation and double validation improve accuracy. The combination of

electronic stamping with blockchain allows for complete transparency and

immutability of documentary traces, which is especially important for customs

and legal control. And the phased implementation with training guarantees smooth

adaptation of the system without disruptions in real port traffic.

Tab. 5

Key measures for implementing electronic

document exchange in the port of Tianjin

|

№ |

Component |

Description |

Functional

role |

|

1 |

Centralized

platform "Single Window" |

A single web interface for all participants to

interact: FCR, customs, TOS, agents |

Unification of processes, reduction of duplication,

centralized access |

|

2 |

Standardization of

formats (XML/JSON) and API |

Use of templates, RESTful API with TLS and OAuth 2.0 |

Seamless integration of systems, data protection |

|

3 |

Automatic creation

of Shipping Order |

Automatic copying of data from FCR to SO |

Reducing errors, speeding up document preparation |

|

4 |

Integrated electronic customs stamping |

Electronic stamping by customs in the "Single

Window" |

Refusal from papers, instant status transfer |

|

5 |

Automatic

notifications and SLA control |

SMS/email notifications, timers to meet deadlines |

Ensuring efficiency, preventive

management |

|

6 |

Double

data validation |

"Hard" - blocks, "soft" - prompts |

Improving data reliability, reducing the number of

errors |

|

7 |

Distributed transaction log |

Blockchain or DLT to record all actions |

Transparency, secure change history, audit |

|

8 |

Gradual implementation and training |

Pilot stages, trainings, feedback collection |

Minimizing implementation risks, user adaptation |

As a result of the analysis of current

bottlenecks in the FCR and Shipping Order exchange procedure in the Port of

Tianjin and the formulation of a number of recommendations aimed at creating a

single digital space for all chain participants, a structure based on the

principles of interoperability, security and increased efficiency of document

processing is presented in Figure 5.

The implementation of these recommendations will

allow particularly the Port of Tianjin to provide a fully digital, transparent,

and controlled document flow - from the moment the cargo is received by the

forwarder to the actual mooring of the vessel-reducing delays and downtime to a

minimum.

Estimation of

the expected economic effect

The analysis shows that the average vessel

demurrage rate at the Tianjin port is about 500 USD/hour. In the current

environment, due to delays in Shipping Order verification, the "grace

period" increases to 14-16 hours, while after the introduction of a single

electronic window and automation of document flow, the expected delay will be

reduced to 4-6 hours. Based on the difference of 9 hours (14-5), the savings in

downtime per ship call will be approximately USD 4,500. At 120 calls per year, this

translates into direct savings of about USD 540,000 in downtime tariffs alone.

Fig. 5. Implementation roadmap for a centralized

single-window

and automated document-exchange system

In addition, reducing the 'grace period'

increases the port's overall throughput by 5-7%, equivalent to servicing an

extra 6-8 vessels per month. At an average freight rate of USD 50,000 per

vessel, calculated annually, this equates to an additional revenue of USD 3-4

million. Therefore, the total economic impact of optimizing document flow,

including direct savings on downtime and revenue generated by increased

traffic, can exceed USD 4 million per year.

In order to quantify the impact of procedural

delays on the total vessel downtime in the port of Tianjin and monitor the risk

of exceeding the "grace period," it is advisable to build an

analytical model that takes into account the individual components of the

document flow. Each of these stages - issuance of the FCR, customs clearance

and stamping of the Shipping Order, verification of documents in the port

system, and berth slot assignment - has its own average execution time and its

own variance. By combining them into an aggregate random variable, we can

estimate not only the expected downtime, but also the probability of a critical

exceedance of the permissible interval.

For an analytical description of the logistics

process of vessel registration and berthing, let us denote the main stages that

constitute the total processing time:

-

TFCR - time from

cargo reception to issuance of the Forwarder’s Cargo Receipt (FCR);

-

𝑇clear - time required for customs clearance and

stamping of the Shipping Order;

-

𝑇ver - time for document verification in PCS/TOS systems

(Port Community System / Terminal Operating System);

-

𝑇slot - time spent waiting for and being assigned a

berth slot.

The total vessel idle time associated with the

port entry process is then modeled as the sum of

these components:

![]() . (1)

. (1)

This equation provides a structural

decomposition of the turnaround time and serves as the basis for probabilistic modeling.

To incorporate variability and uncertainty

inherent to port operations, we treat each component 𝑇𝑖 as a random variable. Specifically, we assume

that:

-

еach 𝑇𝑖 follows a normal distribution with mean 𝜇𝑖 and variance 𝜎2𝑖;

-

variables are

mutually independent, since they reflect distinct administrative or logistical

phases.

Formally:

![]() . (2)

. (2)

Due to the additivity and independence of

normally distributed variables, the total processing time 𝑇total is also normally distributed, with the following

parameters:

, (3)

, (3)

where: 𝜇𝑖 - expected

duration of stage 𝑖, 𝜎2𝑖 - variance of

stage 𝑖.

This probabilistic model enables us to quantify

both the expected delay and the dispersion around the mean, which are critical

for reliability assessment.

Ports often define a grace period threshold,

denoted 𝑇∗,

representing the maximum allowable time for documentation and berthing before

penalties or surcharges apply.

We aim to estimate the probability that the

total time exceeds this threshold:

, (4)

, (4)

where Φ(⋅) - cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the

standard normal distribution.

This expression quantifies the risk of process

overrun, which can be used by port authorities and operators to set buffer

times, prioritize automation, or revise scheduling policies.

Beyond operational risks, excessive turnaround

time directly translates into monetary losses due to vessel idle charges. Let 𝑐rate denote the per-hour cost of vessel idle time (e.g.,

USD/hour). Then, the expected financial loss due to delays is modeled as follows:

![]() . (5)

. (5)

This formulation represents the expected value

of the positive deviation of total processing time above the grace period,

multiplied by the unit cost of delay. It corresponds to the area under the tail

of the distribution beyond 𝑇∗, weighted by cost.

Since 𝑇total∼𝑁(𝜇sum, 𝜎2sum), the above expectation can be numerically evaluated

or approximated using known results for truncated normal distributions.

Given empirical estimates μi and σi from observed data (e.g., from port operations logs),

this model enables the computation of:

- expected processing time;

- probability of exceeding the grace period;

- expected economic loss due to idle time.

These results can be represented as simulation

outputs to compare scenarios with and

without automation, assess the impact of parameter changes, or identify

bottlenecks.

Thus, this model can be used not only to

calculate the average downtime and determine the probability of exceeding the

optimal "grace period". It also helps to estimate economic losses and

obtain an estimate of the direct financial costs of downtime tariffs. In

practice, by substituting the empirically determined 𝜇𝑖 and 𝜎𝑖, we get the estimated cost of delays and can compare

it with the expected savings from the introduction of an electronic window and

automation of document exchange.

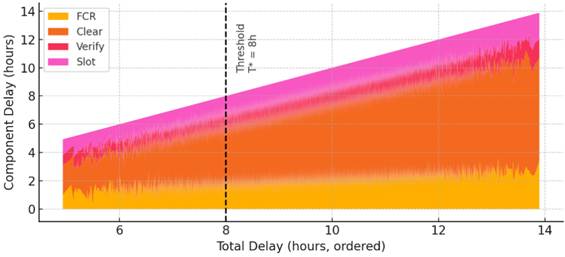

To illustrate how the individual stages of the

document flow procedure affect the total vessel downtime, a stack plot of the

total time and contribution of each component (FCR, customs clearance,

verification, slot assignment) was generated tо allows to clearly view of which links in the chain

become bottlenecks in different scenarios, Figure 6.

Fig. 6. Stacked component contributions to total delay

As can be seen from the graph, the largest

amount of delays is generated by the customs clearance stage (Tclear),

while the contribution of other procedures remains relatively small. The

threshold of 𝑇∗ = 8 hours

clearly separates "acceptable" downtime from those that require

urgent intervention to optimize the process.

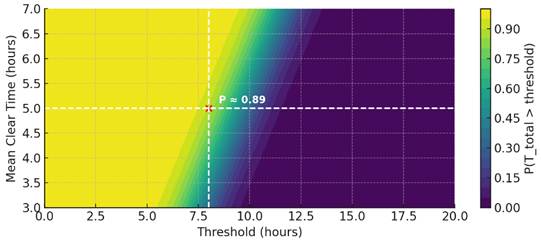

To assess the risk of exceeding the permissible

"grace period" depending on the choice of the threshold and the

average customs clearance time, a contour graph is shown in Figure 7. It allows

us to identify the parameters under which the probability of downtime becomes

critical.

Fig. 7. Probability of exceeding the total delay

depending on the threshold value

and average customs clearance time

Probability of exceeding the threshold Ttotal

as a function of Threshold (hours) and average customs clearance time (Mean

Clear Time, hours). The white dashed lines mark the point (Threshold = 8 hours,

Mean Clear Time = 5 hours) with P ≈ 0.89.

The contour plot shows that with an average

customs clearance time of 5 hours, an increase in the threshold to 8 hours is

accompanied by a probability of more than 89% of exceeding the "grace

period". This confirms that reducing the average clearance time is an

extremely effective way to reduce the risk of downtime.

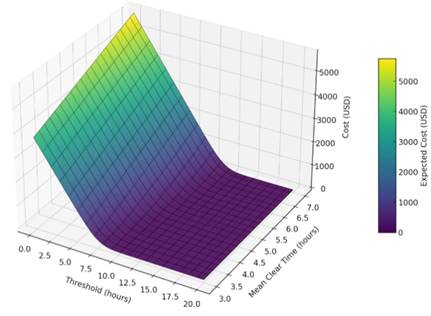

To quantify the financial losses due to port

delays, a graph was plotted in Figure 8 showing the expected cost of downtime

(USD) as a function of simultaneous changes in the threshold value and average

customs clearance time.

Fig. 8. Expected cost of vessel downtime (USD) as a

function of threshold (hours)

and Mean Clear Time (hours)

The graph shows that minimum costs are achieved

at a threshold of about 5-6 hours with an average customs time of ≤4

hours. On the contrary, postponement of both parameters leads to a

multiplicative increase in losses, and the cost of downtime can exceed 500,000

USD for extreme scenarios. This emphasizes the importance of simultaneously

optimizing both parameters at the port.

4. DISCUSSION

During the analysis of document flow procedures

in the Port of Tianjin, we found that the main bottlenecks are discrepancies

between the FCR and the Shipping Order, delays in customs stamping, and manual

verification of documents in PCS/TOS. Interviews with operators and statistical

analysis have shown that the average time from issuing an FCR to assigning a

berthing instruction can reach 12-16 hours, which significantly exceeds the

regulatory "grace period" and leads to financial losses for shipowners

and freight forwarders. At the same time, terminal practice has demonstrated

the high efficiency of integrated APIs and automatic notifications, but these

solutions cover only certain stages, while the lack of a single window slows

down the final processing speed.

An economic analysis shows that the

implementation of Single Window and automation of data transfer from FCR to

Shipping Order will reduce total downtime by 8-10 hours and reduce the cost of

vessel demurrage rates by approximately USD 4,500 per event. The combination of

such technical solutions as rigorous data validation, blockchain audit, and SLA

monitoring creates the preconditions not only for increasing speed but also for

improving the transparency and reliability of the entire chain of logistics operations.

5. CONCLUSION

The analysis of the document flow in the port of

Tianjin showed that the traditional two-stage mechanism - FCR as a confirmation

of cargo acceptance and stamped Shipping Order as the basis for mooring - works

correctly in the regulatory field of the PRC, but creates significant delays

(up to 14-16 hours) due to data discrepancies, waiting for customs stamping,

and manual checks in PCS and TOS. These delays lead to an increase in tariff

costs for vessel downtime and exceeding the "grace period," which

limits the port's throughput.

The proposed system of a single electronic

window with automated exchange of FCRs and Shipping Orders, standardized

exchange formats (XML/JSON, REST API), strict data validation, and blockchain

audit will reduce the total time from issuing an FCR to a berthing instruction

to 4-6 hours. This will save more than USD 540,000 in downtime tariffs and

increase throughput by 5-7%, generating a few million in additional annual

revenue.

The introduction of the Single Window,

integration of customs and port IT systems, automatic alerts, and SLA

monitoring will not only increase the efficiency and transparency of

operations, but also lay the foundation for further digitalization of the port

ecosystem - with the development of intelligent mooring planning algorithms,

what-if analytics, and smart contracts on the blockchain. In this way, Tianjin

Port will be able to strengthen its leadership position in the region and

become a model of an efficient new generation smart harbor.

References

1.

Zeng F., A. Chen, S. Xu, H.K. Chan, Li Y. 2025.

"Digitalization in the maritime logistics industry: A systematic

literature review of enablers and barriers." Journal of Marine Science

and Engineering 13(4): Article 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13040797.

2.

Fruth M., F. Teuteberg. 2017. "Digitization

in maritime logistics – What is there and what is missing?" Cogent

Business & Management 4(1). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1411066.

3.

Jović M., E. Tijan, S. Aksentijević, A. Pucihar. 2024. "Assessing the Digital Transformation

in the Maritime Transport Sector: A Case Study of Croatia." Journal of

Marine Science and Engineering 12(4): 634. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12040634.

4.

Liu S.K. 2021. "Research on the circulation

of maritime documents based on blockchain technology." IOP Conference

Series: Earth and Environmental Science 831: 012066. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/831/1/012066.

5.

Alahmadi D., F. Baothman,

M. Alrajhi, F. Alshahrani, H. Albalawi.

2022. "Comparative analysis of blockchain technology to support digital

transformation in ports and shipping." Journal of Intelligent Systems

31(1): 55-69. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/jisys-2021-0131.

6.

González-Cancelas N., B. Molina Serrano, F. Soler-Flores,

A. Camarero-Orive. 2020. "Using the SWOT Methodology to Know the Scope of

the Digitalization of the Spanish Ports." Logistics 4(3): 20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics4030020.

7.

Heilig L., S. Voß. 2017.

"Information systems in seaports: a categorization and overview." Information

Technology and Management 18: 179-201. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-016-0269-1.

8.

Camarero Orive A., J.I.P. Santiago, M.M.E.-I. Corral,

N. González-Cancelas. 2020. "Strategic Analysis of the Automation of

Container Port Terminals through BOT (Business Observation Tool)." Logistics

4(1): 3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics4010003.

9.

Lee H., N. Aydin, Y. Choi, S. Lekhavat, Z. Irani. 2018. "A decision support system

for vessel speed decision in maritime logistics using weather archive big

data." Computers & Operations Research 98: 330-342. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2017.06.005.

10.

Patil G.R., P.K. Sahu. 2016. "Estimation of

freight demand at Mumbai Port using regression and time series models." KSCE

Journal of Civil Engineering 20(5): 2022-2032. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-015-0386-0.

11. Al-Deek H.M. 2001. "Which method is better for developing

freight planning models at seaports - Neural networks or multiple

regression?" Transportation Research Record 1763(1): 90-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3141/1763-14.

12. Munim

Z.H., C.S. Fiskin, B. Nepal, M.M.H. Chowdhury. 2023. "Forecasting

container throughput of major Asian ports using the Prophet and hybrid time

series models." The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics

39(2): 67-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsl.2023.02.004.

13. Yu

H., X. Cui, X. Bai, C. Chen, L. Xu. 2025. "Incorporating graph theory and

time series analysis for fine-grained traffic flow prediction in port

areas." Ocean Engineering 335: 121693. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.121693.

14. Morales-Ramírez

D., M.D. Gracia, J. Mar-Ortiz. 2025. "Forecasting national port cargo

throughput movement using autoregressive models." Case Studies on

Transport Policy 19: 101322. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2024.101322.

15. Wang

J., K. Liu, Z. Yuan, X. Yang, X. Wu. 2024. "Simulation modeling of

super-large ships traffic: Insights from Ningbo-Zhoushan Port for coastal port

management." Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 138:

103039. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2024.103039.

16. Chu Z., n R. Ya, S. Wang. 2025.

"Vessel arrival time to port prediction via a stacked ensemble

approach: Fusing port call records and AIS data." Transportation

Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 176: 105128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2025.105128.

17. Huang

H., Q. Yan, Y. Yang, Y. Hu, S. Wang, Q. Yuan, X. Li, Q. Mei. 2024.

"Spatial classification model of port facilities and energy reserve

prediction based on deep learning for port management – A case study of

Ningbo." Ocean & Coastal Management 258: 107413. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2024.107413.

18. Pham

T.Y., P.N. Nguyen. 2025. "A Data-Driven framework for predicting ship

berthing time and optimizing port operations at Tan Cang Cat Lai Port,

Vietnam." Case Studies on Transport Policy 20: 101441. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2025.101441v.

19. Das

D., A. Saxena. 2025. "Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on freight volume,

revenue and expenditure of Deendayal Port in India: An ARIMA forecasting

model." Multimodal Transportation 4(2): 100201. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.multra.2025.100201.

20. Abd

Rahim N., R. Ahmad Zaki, A. Yahya, W. Wan Mahiyuddin. 2024. "Acute effects

of air pollution on cardiovascular hospital admissions in the port district of

Klang, Malaysia: A time-series analysis." Atmospheric Environment

333: 120629. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120629.

21. Guo

J., Z. Jiang, J. Ying, X. Feng, F. Zheng. 2024. "Optimal allocation model

of port emergency resources based on the improved multi-objective particle

swarm algorithm and TOPSIS method." Marine Pollution Bulletin

209: 117214. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.117214.

22. Darwich

M., J. Bakonyi. 2025. "Port infrastructures and the making of historical

time in the Horn of Africa: Narratives of urban modernity in Djibouti and

Somaliland." Cities 159: 105781. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2025.105781.

23. Guo

J., W. Wang, C.W. Kwong, Y. Peng, Z. Xia, X. Li. 2025. "Predicting water

demand for spraying operations in dry bulk ports: A hybrid approach based on

data decomposition and deep learning." Advanced Engineering

Informatics 65: 103313. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2025.103313.

24. Cuong

T.N., H. Kim, S. You, D.A. Nguyen. 2022. "Seaport throughput forecasting

and post COVID-19 recovery policy by using effective decision-making strategy:

A case study of Vietnam ports." Computers & Industrial Engineering

168: 108102. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108102.

25. Jovanović

M., N. Kostić, I.M Sebastian., T. Sedej. 2022. "Managing a

blockchain-based platform ecosystem for industry-wide adoption: The case of TradeLens." arXiv. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.04206.

26. Chang

Y., E. Iakovou, W. Shi. 2019. "Blockchain in global supply chains and

cross-border trade: A critical synthesis of the state of the art, challenges,

and opportunities." arXiv. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1901.02715.

27. Yang

C.-S. 2019. "Maritime shipping digitalization: Blockchain-based technology

applications, future improvements, and intention to use." Transportation

Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 131: 108-117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2019.09.020.

28. Guan

P., L.C. Wood, J.X. Wang, L.N.K. Duong. 2024. "Blockchain adoption in the

port industry: a systematic literature review." Cogent Business &

Management 11(1). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2431650.

29. Gondia A., A. Moussa, M. Ezzeldin,

W. El-Dakhakhni. 2023. "Machine learning-based

construction site dynamic risk models." Technological Forecasting and

Social Change 189: 122347. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122347.

30. Ni

L., E. Irannezhad. 2023. "Performance analysis

of LogisticChain: A blockchain platform for maritime

logistics." Computers in Industry 154: 104038. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2023.104038.

31. Shin

S., Y. Wang, S. Pettit, W. Abouarghoub. 2023.

"Blockchain application in maritime supply chain: a systematic literature

review and conceptual framework." Maritime Policy & Management

51(6): 1062-1095. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2023.2234896.

32. Karakaş

S., A.Z. Acar, B. Kucukaltan. 2021. "Blockchain

adoption in logistics and supply chain: a literature review and research

agenda." International Journal of Production Research 62: 1-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2021.2012613.

33. Melnyk O., S. Onyshchenko, O. Onishchenko, Y. Koskina, O. Lohinov, O. Veretennik, Stukalenko O. 2024. "Fundamental

concepts of deck cargo handling and transportation safety." European

Transport - Trasporti Europei

98: 1-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48295/ET.2024.98.1.

34. Melnyk

O., O. Onishchenko, O. Drozhzhyn, O. Pasternak, M. Vilshanyuk, S. Zayats, Shcheniavskyi

G. 2024. "The ship safety evaluation and analysis on the multilayer model

case study." E3S Web of Conferences 501: Article 01018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202450101018.

35. Melnyk

O., I. Petrov, T. Melenchuk, A. Zaporozhets, S. Bugaeva, O. Rossomakha.

2025. "Causal model and cluster analysis of marine incidents: Risk factors

and preventive strategies." Studies in Systems, Decision and Control

580: 89-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-82027-4_6.

36. Nagurney

A., I. Pour, B. Kormych. 2024. "Integrated crop

and cargo war risk insurance: Application to Ukraine." International

Transactions in Operational Research. Advance online publication. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/itor.70038.

37. Kobets

V., I. Popovych, S. Zinchenko, P. Nosov, O. Tovstokoryi,

K. Kyrychenko. 2023. "Control of the pivot point position of a

conventional single-screw vessel." CEUR-WS.org 3513: 130-140. DOI: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3513/paper11.pdf.

38. Zinchenko S., K. Kyrychenko, O. Grosheva, P. Nosov, I. Popovych, o P. Mamenk. 2023.

"Automatic reset of kinetic energy in case of inevitable collision

of ships." IEEE Xplore: 496-500. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ACIT58437.2023.10275545.

39. Zinchenko

S., O. Tovstokoryi, V. Mateichuk, P. Nosov, I. Popovych,

V. Perederyi. 2024. "Automatic prevention of the

vessel’s parametric rolling on the wave." CEUR-WS.org 3668: 235-246.

DOI: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3668/paper16.pdf.

40. Melnyk

O., Y. Bychkovsky, O. Onishchenko, S. Onyshchenko, Y. Volianska. 2023.

"Development the method of shipboard operations risk assessment quality

evaluation based on experts review." Studies in Systems, Decision and

Control 481: 695-710. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35088-7_40.

41. Zhikharieva V. 2025.

"Benchmarking of intangible assets in the shipping industry." Transactions

on Maritime Science 14(1). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7225/toms.v14.n01.w04.

42. Aboul-Dahab

K.M. 2025. "Investigating the efficiency of the Egyptian sea port

authorities using the data envelopment analysis (DEA)." Journal of

Maritime Research 22(1): 378-384.

43. Osadume R.C., E.O. University,

D.B. Ogola. 2025. "Impact of Covid’19 pandemic on ports operations in

Nigeria." Journal of Maritime Research 22(1): 224-231.

44. Nwoloziri C.N., I.C. Nze,

A. Hlali, u T.C. Nwachukw,

T.C. Nwokedi. 2025. "Estimation of cost of delays on vessel operations in

container terminals of Apapa seaports." Journal of Maritime Research

22(1): 217-223.

45. Varbanets R., D. Minchev,

I. Savelieva, A. Rodionov, T. Mazur, S. Psariuk, V. Bondarenko. 2024.

"Advanced marine diesel engines diagnostics for IMO decarbonization

compliance." AIP Conference Proceedings 3104(1): Article 020004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0198828.

46. Luidmyla L.N., Y.O.

Taras, V.H. Oleksandr. 2025. "New approach in models for managing the

vessel’s unloading process." Journal of Shipping and Trade 10: 5.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-025-00195-2.

47. Nikolaieva L.L., T.Y. Omelchenko,

O.V. Haichenia. 2025. "Formalization of hybrid

systems models for port terminal management with considering of key performance

indicators." Engineering Reports 7(1): Article e70004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.70004.

Received 11.06.2025; accepted in revised form 15.09.2025

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License