Article

citation information:

Granà, A., Macioszek,

E., Tumminello, M.L. Data-driven trend analysis on sustainable and smart

mobility in Italy. Scientific Journal of

Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2025, 129, 75-95. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2025.129.5

Anna GRANÀ[1], Elżbieta MACIOSZEK[2], Maria Luisa TUMMINELLO[3]

DATA-DRIVEN TREND

ANALYSIS ON SUSTAINABLE AND SMART MOBILITY IN ITALY

Summary. This paper presents a

data-driven trend analysis of sustainable, shared, and zero-crash mobility

within the Italian context, serving as a starting point for research aimed at

assessing the current level of knowledge regarding novel mobility concepts and challenges.

A pilot sample of 30 respondents over the age of 60 years old was selected for the

prototype survey interview conducted to evaluate their knowledge and

perceptions concerning the transition towards sustainable and smart mobility.

Key findings from the interviews provided valuable insights into older adults'

understanding of the topic and their expectations, offering a foundation for

future policies and inclusive initiatives to contextualize Italian experiences

within global trends in sustainable mobility for urban planners and

policymakers.

Keywords: sustainability, cities, smart mobility, road infrastructure, survey interview

1.

INTRODUCTION

Sustainable urban mobility is rapidly advancing

driven by digital innovations and growing environmental awareness, with goals

to reduce emissions and improve road system efficiency and accessibility in

built environments [1,2]. Transforming road infrastructure with smart

technologies and ensuring resilience against challenges like climate change and

urbanization are increasingly essential [3,4]. As urbanization continues – with

over 60% of the European population projected to live in cities – issues such

as traffic congestion, road safety, infrastructure deterioration, and air

pollution have become critical, emphasizing the urgent need for smart mobility

solutions [5]. Road infrastructure plays a vital role in shaping urban dynamics

by impacting economic growth, promoting social inclusion and access to public

transportation, and ensuring environmental sustainability [6]. Well-designed

road systems enhance accessibility for diverse users, emphasizing the need to

understand how evolving infrastructure influences user experiences and societal

trends while supporting eco-friendly innovations for sustainable and safe

mobility [7,8]. To become smarter, road infrastructure should incorporate four

core aspects: self-awareness via real-time monitoring of road conditions and

traffic; interactive information sharing among connected intelligent devices,

sensor networks, and databases; self-adaptation for automatic adjustments to

traffic variations; and energy harvesting from road pavements to power smart

systems [4,9]. In this context, road infrastructure needs advanced

communication, sensors, and data analytics, with smart traffic systems

utilizing real-time data to improve traffic flow and fuel efficiency [9].

Innovations like adaptive traffic signals and vehicle-to-everything

communication can enhance safety and efficiency by enabling communication

between vehicles and infrastructure [10]. The expansion of Big Data via smart

devices and digital communities also allows for extensive data collection while

safeguarding privacy and data quality [7]. However, a holistic design approach

is essential to ensure the resilience of road infrastructure, maintaining the

functionality of roads and intersections under stress [11]. Circularity in road

construction and management is crucial, focusing on sustainable materials,

resource recycling, and waste minimization to balance current needs with future

sustainability [12]. Key questions still include making mobility authentically

smart, developing resilient infrastructure, and integrating circularity with

emerging technologies. Adapting to new mobility models is vital for the future

of cities and residents' well-being.

Based on the above, this study examines trends

in sustainable, shared, and zero-crash mobility in Italy to explore the dilemma

between traditional road network designs and modern urban mobility challenges.

As Italian cities rapidly expand and evolve, it is crucial to adapt road

infrastructure to meet changing transportation needs. Data-driven trend

analysis prompted us to initiate research to assess the current level of

knowledge surrounding sustainable and smart mobility concepts. From an

inclusive perspective, we conducted a prototype survey interview with a pilot

sample of respondents over 60 years old to evaluate their awareness of

sustainable and smart mobility, as well as their perceptions and experiences

related to the topic. The key findings from the face-to-face interview phase

provided valuable contextual insights, deepening our understanding of older

adults' needs and expectations regarding urban mobility. These insights can

serve as a foundation for developing effective policies and inclusive initiatives

that address the specific needs of older adults, while also contextualizing

Italy's experiences within global trends to contribute to the discourse on

sustainable mobility for urban planners and policymakers facing similar

challenges.

After reviewing mobility concepts and

data-driven analysis of sustainable, shared, and zero-crash mobility in Italy

(Section 2), the research methodology involving surveys with elderly

participants is detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents and analyses the

results, with conclusions in Section 5.

2. INSIGHTS

FROM MOBILITY CONCEPTS AND DATA TRENDS

Urban mobility in Italy is evolving to address

modern challenges and foster healthier and more interconnected communities [13,14].

As urban populations grow and transportation demands increase, sustainable

mobility policies are essential to efficiently manage infrastructure and adapt

to new mobility trends, improving residents' well-being. Smart urban planning

is vital in integrating diverse transport modes – like buses, bicycles, and

shared systems – into a cohesive, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable

network [13-15]. Investments in road infrastructure should encourage active

lifestyles, while advances in connected and automated mobility aim to enhance

traffic management and safety, leading to a more efficient urban transport

system [9]. Data collection is key to understanding mobility trends and creating liveable

cities. In Italy, a centralized system aggregates local authorities' data to

produce annual reports that compare mobility patterns over time (e.g., [14,15]). The following sections analyze

trends in sustainable, shared, and zero-crash mobility in Italy to assess the

current situation.

2.1. Trends in

Sustainable Mobility

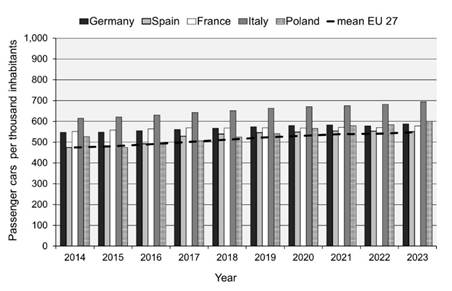

Mobility trends indicate

that Italy has a high motorization rate, with about 694 passenger cars per

thousand inhabitants in 2023 [13]. Fig. 1, based on Eurostat data as of January

2025, provides a benchmark for comparing vehicle ownership and usage across EU

countries [13].

Fig. 1.

Motorization rates in the EU 27

Source: data

elaborated by the authors from [13]

In

2023, Italy had the highest car ownership in the EU, surpassing the average of

just under 600 cars per thousand inhabitants. Fig. 2 compares passenger car

counts per thousand inhabitants in Italy and major EU economies like France,

Germany, Spain, and Poland over the years. Urban mobility data indicate rising

vehicle motorization rates in Italian cities, with progress towards sustainable

transportation lagging, emphasizing the need for stronger efforts to promote

greener options. Although use of bicycles, public transport, and electric

vehicles is increasing, the share of low-emission cars remains relatively

modest [14].

Fig. 2.

Passenger cars per thousand inhabitants in European countries.

Note: mean EU is the mean value recorded in the EU countries

per year during the considered timeframe

Source: data

elaborated by the authors from [13]

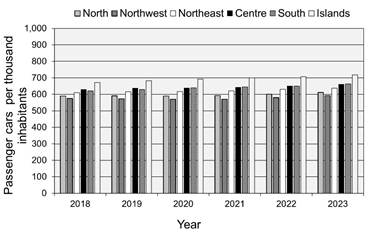

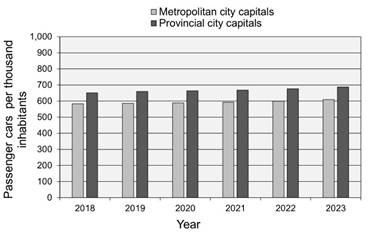

Fig. 3 shows Italy's motorization rates from

2018 to 2023, measured as passenger cars per thousand inhabitants, categorized

by geographical area and city type – metropolitan city capitals (larger urban

areas) and provincial capitals (main cities of provinces). Differences among

macro-areas are influenced by variations in road infrastructure and public

transport. Densely populated Italian cities often have lower motorization rates

due to available public transport, walkable environments, and cycling options,

which reduce reliance on private cars and promote sustainable mobility. These

geographical differences in 2023 show variation from previous years [14]:

northern capitals have 612 passenger cars per thousand inhabitants, central

capitals 660, and southern capitals 662 (see Fig. 3a). Larger metropolitan city

capitals average 609 cars per 1,000 inhabitants, while provincial capitals have

687, compared to the overall average of 648 per thousand inhabitants across all

capitals [14]. Cities with extensive public transport, especially in northern

areas (see Fig. 3a) and metropolitan city capitals (see Fig. 3b), tend to have

lower motorization rates due to better public transport options [14]. In 2023,

most Italian metropolitan capitals experienced higher motorization rates

compared to 2018, except Turin, which slightly decreased from 640 to 638 cars

per 1,000 inhabitants. Notably, Southern cities like Naples, Palermo, Messina,

and Catania saw the largest increases [14]. Between 2021 and 2023, vehicle

density – vehicles per kilometre of urbanized area – was about 60% higher in

metropolitan capitals than in provincial capitals [14]. Further details are

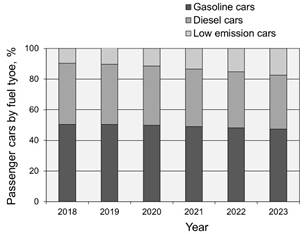

provided in Fig. 4. Fig. 4a features a stacked bar chart illustrating the

annual percentage changes in passenger cars by fuel type – gasoline, diesel,

and low-emission cars (such as gas or bi-fuel, electric, and hybrid) – in

Italian cities from 2018 to 2023 [14,15]. Between 2018 and 2023, the growth of

gasoline cars slowed by about 6%, and diesel cars by 12%, largely driven by a

rise in low-emission vehicles, which accounted for approximately 50% of new

registrations since 2020 [14]. In 2023, Venice has one of the lowest shares of

gasoline cars, while Rome and Milan lead in low-emission vehicle adoption.

Southern cities like Naples, Palermo, and Cagliari also closely follow in

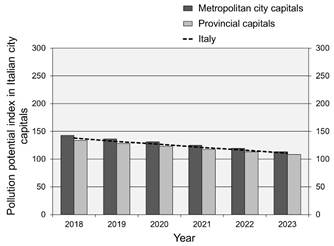

embracing low-emission options [14]. Fig. 4b presents the pollution potential

index of passenger cars by city capital type, evaluating vehicle composition

based on emission class (Euro 1 to Euro 6) and fuel type (gasoline, diesel,

gas, bi-fuel, electric, and hybrid).

|

|

|

(a) |

|

|

|

(b) |

Fig.

3. Motorization rates in

passenger cars per thousand inhabitants in Italy by

(a) geographical area and (b) type of city (metropolitan city capitals and

provincial capitals)

Source: data elaborated

by the authors from [14]

Vehicles

are categorized into high, medium, or low pollutant potential levels: high

(Euro 0 to Euro 3), medium (Euro 4 to Euro 6), and low (gas or bi-fuel,

electric, and hybrid vehicles). Notably, Euro 0 cars, registered before

December 31, 1992, are included, while pre-Euro 4 hybrid cars are excluded from

the low pollutant potential category [14]. The pollution potential index is 100

when high-and low-polluting vehicles are equal in number. Values above 100

indicate more high-polluting vehicles, while values below 100 signify a

dominance of low-polluting vehicles. Overall, data shows a consistent decrease

in pollutant potential over time (see Fig. 4b). However, in southern cities

with older vehicle fleets, the indicator remains higher in 2023 compared to the

North and Centre, where there's a closer balance between polluting vehicles and

low-emission options compared to the South [14,15].

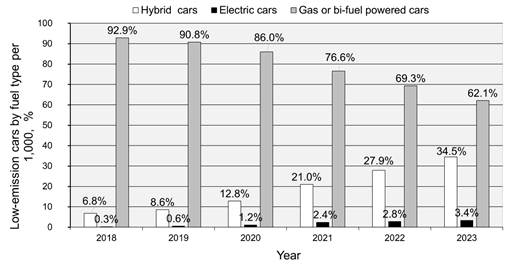

The

energy transition is advancing gradually, with electric cars remaining a small

proportion compared to gasoline vehicles. Since 2019, the adoption of

low-emission cars has increased, mainly due to the rise of hybrid vehicles

combining electric and combustion engines.

|

|

|

(a) |

|

|

|

(b) |

Fig.

4. Environmental indicators in Italy (2018-2023): (a) Passenger cars

percentages by fuel type; (b) Pollution potential index of cars by city

capital, compared to Italy's overall trend based on averages from provincial

and metropolitan city capitals

Source: authors' elaboration based on [14,15]

However,

the largest segment continues to be gas (methane or LPG) and bi-fuel cars,

still classified as fossil fuel-powered (see Fig. 5). Italy has the highest car

ownership in the EU but is gradually transitioning towards sustainable

transportation. Despite the increasing adoption of low-emission vehicles, older

and more polluting cars are still widespread, particularly in the South. Recognizing

regional disparities underscores the urgent need to enhance public

transportation and promote shared mobility solutions. Ongoing monitoring, data

collection, and strategic planning are crucial to fostering greener mobility in

Italian cities.

Fig. 5.

Percentages of low-emission cars by fuel type per 1,000 cars

Source: data

elaborated from the authors from [14]

2.2. Trends in

Shared Mobility

Shared

mobility is transforming traditional transportation into a more innovative and

environmentally friendly model [16]. Bike-sharing, car-sharing, carpooling,

scooter-sharing, and on-demand services improve efficiency, decrease dependence

on private vehicles, and promote conservation and equity through shared use

rather than ownership [17].

Bike-sharing

services include: 1) Station-based systems – comprising low-tech options, some

outdated but still functional, which rely on codes or keys at georeferenced

stations – and dock-based systems where bikes are secured in racks and accessed

with magnetic cards; 2) Free-floating fleets accessible anywhere within the

area; 3) GPS-based systems that reserve or unlock bikes via an app; and 4)

Peer-to-peer sharing offered by individuals through specialized platforms.

Car-sharing allows users to rent vehicles for trips, promoting cost-sharing and

reducing ownership burdens by treating cars as temporary, consumable assets

[17]. Types of car-sharing include 1) Station-based services with fixed pickup

and return stations; 2) Free-floating services, allowing users to pick up and

return cars within the operational area; and 3) Peer-to-peer sharing, where

private owners share their cars via a platform without involving rental

companies. Carpooling involves informal arrangements where individuals share a

vehicle on the same route, with drivers providing the car and passengers

sharing fuel and travel costs, with instant carpooling via platforms and apps

being the most common [17]. Scooter-sharing services, like bike-sharing,

involve renting scooters for travel within the service area and typically

include a helmet stored in the scooter. On-demand transportation services –

such as taxis and modern apps like Uber – enable users to book shared trips

quickly via smartphones [17]. All sharing mobility services possess key characteristics

that enhance effectiveness and user experience [18]. Modern mobility services

prioritize shared transportation, operating alongside or after private vehicles

like public transit and taxis. Using digital platforms and GPS, they connect

drivers and passengers for on-demand, flexible, and scalable options, helping

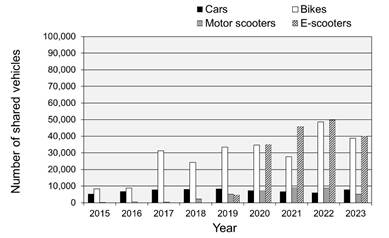

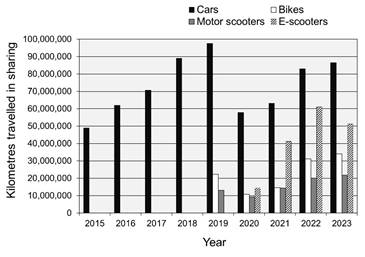

to reduce urban congestion and CO2 emissions. Fig. 6 shows the

supply and demand trends for shared mobility in Italy from 2015 to 2023,

including the number of vehicles for car-sharing, bike-sharing, motor scooters,

and e-scooter sharing (Fig. 6a), as well as mileage data (Fig. 6b). Notably,

e-scooter sharing services began in 2019, saw significant growth until 2022,

and experienced a decline in 2023 [19].

In

2023, shared mobility in Italy totalled nearly 200 million kilometres travelled,

a 45% rise since 2021 in the post-COVID period (see Fig. 6b). A further 7%

increase is projected for 2024 based on first-quarter data [19]. The vehicle

composition in 2023 included bikes (14%), e-bikes (28%), motor scooters (5%),

e-scooters (44%), electric cars (3%), and gasoline cars (6%), reflecting a

shifting landscape in shared mobility trends [19].

|

|

|

(a) |

|

|

|

(b) |

Fig. 6. Trends of supply and demand for shared mobility

in Italy:

(a) Number of shared vehicles, (b) Kilometres travelled in sharing.

Note: car-sharing and bike-sharing services include both free-floating

and station-based options

Source: data elaborated from

the authors from [19]

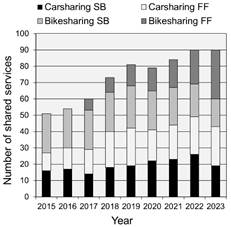

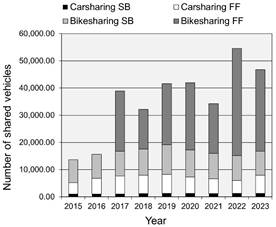

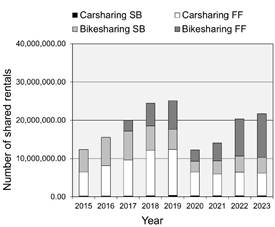

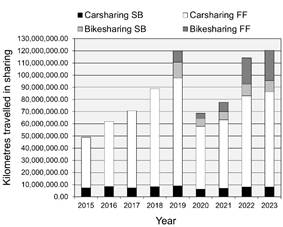

Fig.

7 shows the supply and demand trends for car-sharing and bike-sharing in Italy

(2015-2023), focusing on free-floating (FF) and station-based (SB) models. The

number of FF

car-sharing services is increasing, while SB car-sharing decreased by 27% in

2023 compared to 2022 and by 17% compared to 2021 (Fig. 7a). Since 2020, the

number of vehicles in FF

car-sharing has been recovering, whereas the vehicle count in SB car-sharing

has remained stable at around 1,200 vehicles (Fig. 7b).

SB

car-sharing achieved approximately 300,000 rentals in each of the last two

years, despite a slight reduction in FF car-sharing during the same period

(Fig. 7c). Meanwhile, distances travelled by FF car-sharing increased by 52% in

2023 compared to 2020, reaching about 78 million kilometres in 2023,

demonstrating greater resilience to the effects of the pandemic (Fig. 7d)

[19].

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

|

|

|

|

(c) |

(d) |

Fig. 7. Trends of supply and demand for car-sharing e

bike-sharing in Italy:

(a) Number of shared services, (b) Number of shared vehicles, (c) Rentals

and (d) kilometres travelled.

Note: Shared services include free-floating (FF) and station-based (SB) models

Source: data elaborated by authors from [19]

The

data shows that FF bike-sharing services increased by 76% in 2023 compared to

2021, while SB services declined by 26% over the same period (Fig. 7a). The

number of bikes in SB services remained stable during the period shown in Fig.

7b. In contrast, bikes in FF services decreased by 26% in 2023 compared to

2022, mainly due to fleet downsizing in major cities like Rome and Milan. The

supply level in 2023 is expected to be maintained through 2024 [19]. Electric

bikes constitute 62% of Italy's shared bicycle fleet in FF services, driven by

the adoption of hourly and daily rental options [19]. Demand for bike-sharing,

particularly in rentals, grew significantly between 2022 and 2023 for FF

services, with further growth forecasted (Fig. 7c) [19]. Additionally,

distances travelled increased by 15% in 2023 compared to the previous year,

totalling around 25 million kilometres in FF bike-sharing (Fig. 7d).

A

questionnaire was distributed to over 10,000 shared mobility users via app

pop-ups, newsletters, and social media to assess perceptions of shared mobility

as public transportation [19]. The survey was designed to mask its objectives

and ensure anonymity, encouraging genuine responses about the benefits of these

services and potential shifting usage preferences. The main feedback showed

that three out of four users expressed positive opinions about the development

of available shared mobility services. Car sharing received only 42% positive

responses, lagging behind other services. Additionally, over 80% of users

indicated that the closure of shared mobility services in their city would

greatly impact their mobility habits. On financial support for vehicle-sharing

services, 63% of users favoured it, 24% agreed with conditions, while only 7%

opposed public funding. Data on on-demand transport services showed that over

600,000 passengers were transported in 2023 [19]. Service offerings increased

significantly, especially in northern regions, tailored to specific contexts

and addressing local mobility needs with both seasonal and year-round options.

2.3. Trends in

Zero-Crash Mobility

Road safety is a shared responsibility among all

road users and professionals. Frequent crashes result in loss of life and

property damage, impacting community safety. Zero-Crash mobility refers to a

transportation system or approach aimed at eliminating road traffic crashes and

fatalities. The goal is to create a safer mobility environment where advanced

safety technologies, intelligent infrastructure, and comprehensive safety

strategies protect all road users like drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and

cyclists [20,21]. Achieving this requires balancing the components of the road

system and their interactions within natural and built environments, as

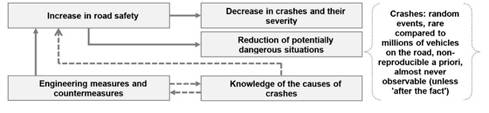

illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Framework for understanding the functionality of

the road safety system

Effective road design should be clear and

intuitive, with suitable slopes and materials that encourage safe vehicle

speeds and smooth traffic flow [20]. While improved safety generally reduces

crashes and their severity, managing road safety remains complex due to the

unpredictable nature of crashes. In this context, Fig. 9 outlines the key

aspects essential for achieving zero-crash mobility.

Engineering measures and countermeasures

significantly impact road safety, which depends on the quality of road

infrastructure and its link to crash frequency. Security pertains to users’

personal feelings of safety and perceptions of infrastructure reliability.

Although safety and security are related, the focus is on assessing road safety

across different infrastructure segments and intersections to identify

effective interventions that enhance overall safety [21].

In Italy, a road crash is defined according to

the 1968 Vienna Convention [22] as an event involving at least one vehicle –

stationary or moving—on a traffic-accessible road resulting in injuries or

fatalities within 30 days.

Fig. 9. The logical pathway of zero-crash mobility.

Data are collected nationally and officially

recorded by law enforcement. This definition serves as a benchmark for

comparing crash data to the first six months of 2019, which is the reference

year for the European Commission's 2030 goal [21]. Compared to 2019, Italy has

globally experienced a decline in road crashes (4.0%), injuries (8.0%), and

fatalities (~7%), reflecting progress towards safer mobility.

Preliminary data for the first half of 2024 show

a slight increase in road crashes causing injuries compared to the same period

in 2023, with crashes (+0.9%), injuries (+0.5%), and fatalities within thirty

days (+4.0%) [22]. This trend suggests that Italy is moving away from European

road safety targets, underscoring ongoing challenges in road safety management

and the need for effective interventions. In the first half of 2024, highway

fatalities decreased by 14.0% compared to the same period in 2023, while

fatalities on urban and rural roads increased by 8.0% and 1.0%, respectively.

Compared to the first half of 2019, highway fatalities declined significantly

by 32.0%, rural road fatalities decreased modestly by 4.0%, but urban road

fatalities rose slightly by 1.0% [22]. However, complete official data for 2024

are needed for a definitive analysis.

Data for the first four months of 2024 indicates

a 3% increase in vehicle kilometres travelled on highways compared to 2023,

driven mainly by a 4% rise in heavy vehicle traffic and a 3% increase in light

vehicle volumes [21,22]. In the first half of 2024, new car registrations

increased by about 5%, and motorcycle registrations rose by 6% compared to the

same period in 2023. However, compared to 2019, new car registrations declined

by 16.5%, while motorcycle registrations increased significantly by 47.5%. Provisional

data for January to June 2024 indicates that 73% of crashes occurred on urban

roads, while rural roads have the highest fatality rate at 47%. On highways,

crashes and fatalities represented 6% and 8%, respectively [22]. Data on

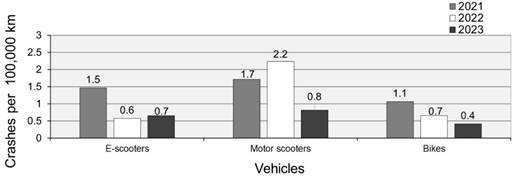

crashes involving personal injuries related to shared micromobility in Italy

has also been collected from insurance company reports and law enforcement,

including user-reported events [22]. Notably, crashes were recorded even

without formal reports or hospitalizations. In 2023, there were 637 recorded

crashes, including one fatal e-scooter crash in Rome. The incidence of crashes

associated with shared micromobility services appears to be decreasing, likely

due to increased user familiarity, with higher rates observed during the

initial months of service. Fig. 10 shows crashes per 100,000 km in Italy for

2021–2023 [19].

Preliminary data reveal contrasting trends

between crashes and shared micromobility usage. To meet Europe's 2030 road

safety goals, Italy needs a comprehensive approach that leverages big data for

detailed analysis and targeted interventions [21].

Fig. 10. Crashes in shared micromobility services per

100,000 km in 2021-2023

Source: data elaborated by the authors from [19]

3.

INVESTIGATION THROUGH A SURVEY INTERVIEW FOR THE ELDERLY: WHAT DO THEY KNOW

ABOUT SUSTAINABLE AND SMART MOBILITY?

Mobility trends in Italy

are increasingly centred on sustainable and smart solutions to enhance

transportation and residents’ quality of life. Understanding the perceptions of

diverse groups, especially the elderly, is essential for developing inclusive

policies. Community surveys can provide valuable insights into their knowledge,

attitudes, and experiences regarding sustainable mobility and related concepts.

This initial investigation aims to promote inclusivity by listening to user

groups that may be marginalized during the digital transition, with ongoing

improvements envisaged.

3.1.

Explaining the Survey Methodology

Recognizing that the

survey interview was in its prototype phase, the authors conducted the research

action following specific steps as follows:

1. The first

step involved designing a structured survey interview that addressed key

aspects of sustainable and smart mobility. The prototype questionnaire

consisted of 16 closed-ended questions, with the first five providing

informational content. These included demographic questions to contextualize

the data, such as age, educational qualifications, gender, cultural identity,

and a question about smart cities to assess participants' understanding of the

concept, expressed in English (see Table 1). Other questions addressed concepts

such as smart mobility, smart roads, shared mobility, road infrastructure,

autonomous vehicles and willingness to use them, car-sharing services,

connected and automated mobility, low-emission cars, and micromobility. Each

question provided a minimum

of three alternative options to guide participants'

responses (see Table 2). The final question concerns participants' preferences

regarding the mode of questionnaire administration (face-to-face interview or

email) to understand their inclinations. Gathering feedback on participants'

preferred delivery methods can facilitate a more personalized and accessible

research approach, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of the surveys and

enabling the optimization of data collection methods for future studies.

2. The

second step involved selecting the pilot sample. It was decided to limit the

administration of the questionnaire to 30 older adults living in urban areas in

Sicily, Italy. Half of the participants would reside in a metropolitan city

with a population exceeding 600,000 but below 700,000, while the other half

would live in a town with a population of approximately 50,000; population

classes were based on official data as of January 1, 2024 [23]). Understanding

participants' diverse backgrounds reveals disparities in mobility knowledge and

access, with older adults in urban areas experiencing different challenges

compared to those in rural areas, where transportation options are often

limited. None of the respondents were engineers or worked in the engineering

field, which resulted in a limited number of interviews during this phase.

3. The third

phase involved conducting face-to-face interviews using the prototype

questionnaire consisting of 16 closed-end questions (see Tables 1,2), with 30

participants over the age of 60 years old who voluntarily agreed to participate. Participants

were assured of anonymity and informed that data would be used solely for

informational purposes. Researchers directly engaged with them, clarifying the

questionnaire and objectives, and encouraged sharing experiences on urban

mobility to identify knowledge barriers and gather insights into older adults'

challenges and opinions.

4. After

administering the questionnaire, the fourth step involved processing the

collected data to ensure accuracy and reliability. Quality checks were

conducted to identify inconsistencies or errors. The data were then coded and

organized into a database to facilitate the analysis; all information was

handled anonymously for privacy reasons, based on the exclusively informational

purpose of the research.

Key findings from elderly

respondents will be presented in the next section.

Tab. 1

The preliminary questions (PQ1 to PQ5) and the

alternative answers

|

No |

Questions |

Alternative answers |

|

PQ.1 |

How old

are you? |

a. Between

60 and 65. b. Over 65

and under 75. c. Over

75. |

|

PQ.2 |

What is

your educational qualification? |

a. High school diploma*. b. Master’s degree. c. PhD. d. I

prefer not to say. |

|

PQ.3 |

What is

your gender? |

a. Male. b. Female. c. I

prefer not to say. |

|

PQ.4 |

How do you

identify your origin? |

a. I am Italian. b. I am European. c. I

prefer not to say. |

|

PQ.5 |

Have you

ever heard of Smart Cities? |

a. Yes, many times. If yes, please specify (news on TV, radio,

documentaries, books, internet) b. No. c. I don’t

know. |

* In the case of a middle school diploma (msd), the answers will also be reported as a separate

category

Tab. 2

The closed-end questions (Q1 to Q11) and the

alternative answers

|

No |

Questions |

Alternative answers |

|

Q.1 |

What does

smart mobility mean? |

a. Smart

mobility represents an intelligent and eco-sustainable transportation

approach that uses digital technologies to optimize mobility. b. Smart

mobility is fast mobility with small-displacement cars. c. Smart

mobility is represented by motorcycles, helicopters, and motorboats. |

|

Q.2 |

What does

Smart Road mean? |

a. A smart

road is a fast-flowing road. b. Smart

roads, or intelligent roads, are road infrastructures equipped with advanced

technologies to monitor traffic, enhance safety, and promote sustainability. c. A

small-sized car, such as a city car. |

|

Q.3 |

How would

you define shared mobility? |

a. Sharing

mobility is a form of transportation exclusively for private vehicles

purchased in installments. b. A

transportation method that uses only public transport and intercity and

metropolitan trains. c. Sharing

mobility allows for the sharing of vehicles and routes, making transportation

more interactive and efficient, while also reducing expenses and consumption

associated with owning a vehicle. Examples include car-sharing and bike-sharing. |

|

Q.4 |

What comes

to mind when you think of road infrastructure? |

a. The

materials used to create a stable and durable road surface. b. In the

context of land transportation, road infrastructure refers to the collection

of road networks and roads. c. The

construction of skyscrapers. |

|

Q.5 |

What is an

autonomous vehicle? |

a. An

autonomous vehicle is a car capable of sensing road conditions and driving

without human intervention. b. A

vehicle that belongs to a single owner. c. A

vehicle designed exclusively for the transportation of heavy goods and

hazardous materials. |

|

Q.6 |

Are you

willing to use an autonomous vehicle? |

a. Yes. b. No. c. Maybe. |

|

Q.7 |

What is a

car-sharing service? |

a. A

support service for the purchase of zero-kilometre vehicles. b. Car

sharing is a service that allows you to rent vehicles for short periods,

sharing the costs and facilitating booking through an app or website. c. A

travel agency that organizes long-distance car tours. |

|

Q.8 |

What does

connected automated mobility mean? |

a.

Connected and automated mobility is synonymous with cooperative mobility in

sharing data and resources to promote congestion. b.

Connected mobility uses technologies for real-time communication, while

automated mobility employs autonomous vehicles. c. A

transportation method based solely on bicycles. |

|

Q.9 |

What is a

low-emission vehicle? |

a. A

vehicle powered by gas or bi-fuel, electric, or hybrid engines. b. A

vehicle that can operate only on solar energy. c. A

vehicle that consumes more fuel than traditional models. |

|

Q.10 |

What comes

to mind when you hear the word “micromobility”? |

a. Light

vehicles for short trips in the city, such as e-scooters. b. Light

air transport. c. Large

cars designed for large families. |

|

Q.11 |

Would you

have preferred to receive the questionnaire via email? |

a. Yes. b. No. c. I

prefer not to answer |

4. THE RESULTS

AND THEIR ANALYSIS

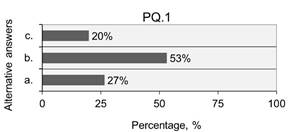

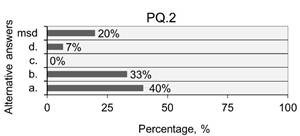

This section highlights

key findings from elderly respondents regarding their perceptions and

experiences with sustainable and smart mobility. Fig. 11 displays responses to

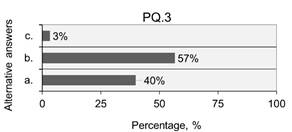

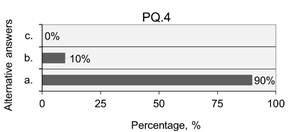

preliminary questions PQ.1,2,3,4 in Table 1.

The data on age (PQ.1)

helped characterize the sample, revealing that 53% of respondents are aged

between 65 and 75. This information is useful for analyzing age-related effects

on understanding and knowledge of contemporary mobility and sustainability issues.

Additionally, PQ.2 explored participants' education levels with four options:

(a) high school diploma, (b) master’s degree, (c) doctorate, and (d) no answer.

This data aims to assess the potential correlation between education and

awareness of the discussed topics. The results showed that 40% of respondents

hold a high school diploma, 33% have a master's degree, none have a PhD, and 7%

chose not to disclose their education level (but 20% possess only a middle

school diploma). Regarding gender (PQ.3), participants were asked to identify

their gender, selecting from male (40%), female (57%), or no answer for the

remaining respondents. This information was used to analyze

potential differences in experience related to the discussed themes. In

response to question PQ.4, 90% indicated they are Italian, and 10% stated they

are European. The origin, or cultural identity, of participants, through three

options by identifying as (a) Italian, (b) European, or (c) choosing not to

indicate their origin, can support the characterization of the socio-cultural

context for the responses given thereafter. Question PQ.5 assessed

participants' familiarity with Smart Cities, revealing that 20% had frequently

heard about the concept through TV or documentaries, although three of them did

not specify their sources. One participant mentioned learning about it from

"work," despite no engineers or industry professionals being involved

in the survey. Conversely, 67% had never heard of smart cities, 10% responded

"I don't know," and the remaining participants did not answer.

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

|

|

|

|

(c) |

(d) |

Fig. 11. The respondents' answers to the preliminary

questions in Table 1 are as follows:

(a) PQ.1 pertains to age, (b) PQ.2 concerns education level, (c) PQ.3 relates

to gender,

(d) PQ.4 addresses cultural identity. Note: Items a, b, c, and d (where

present) are detailed in Table 1; "msd"

stands for middle school diploma

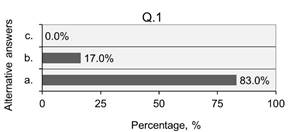

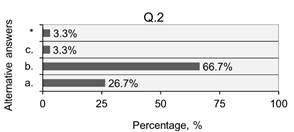

Fig. 12 presents the most significant results

related to questions from Table 2 (e.g., Q.1, Q.2, Q.4, Q.5, Q.8, and Q.9). For

brevity, the remaining questions and their corresponding answers will be

described and discussed only briefly.

In response to the question about the meaning of

smart mobility (Q.1), 83% of respondents recognized it as an intelligent and

eco-sustainable transportation approach that uses digital technologies to

optimize mobility. Conversely, 17% associated smart mobility with speed and

small-displacement cars, potentially due to a lack of familiarity with related

English terms or expressions, which are generally considered part of the

current vocabulary by experts (see Fig. 12a). All the interviewees exclude that

smart mobility is represented by motorcycles, helicopters, and motorboats. In

response to Q.2 (see Fig. 12b), around 27% mistakenly linked the smart road

concept to a fast-flowing road as highways, while around 67% appropriately

associated it with road infrastructures that utilize advanced technologies for

traffic monitoring, safety enhancement, and sustainability, potentially

influenced by the attribute 'intelligent' present in the answer choices (see

Table 2). The remaining respondents were evenly split between choosing a

small-sized car, such as a city car, as an alternative answer, and selecting no

suitable options. Regarding the definition of sharing mobility in response to

Q.3 in Table 2, 80% of respondents agreed on the correct answer (c), which is

that sharing mobility allows for the sharing of vehicles (such as cars and

bikes) and routes, making transportation more interactive and efficient while

also reducing expenses and consumption associated with owning a vehicle.

However, one respondent, unsure, also attributed the concept of sharing

mobility to the first option in Table 1 (i.e., sharing mobility as a form of

transportation exclusively for private vehicles purchased in installments). The

remaining respondents were evenly split among the other two options.

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b) |

|

|

|

|

(c) |

(d) |

|

|

|

|

(e) |

(f) |

Fig. 12. The

answers provided by the respondents to the questions in Table 2:

(a) Q.1 pertains to smart mobility, (b) Q.2 pertains to smart roads, (c) Q.4

pertains to road infrastructure, (d) Q.5 pertains to autonomous vehicles, (e)

Q.8 pertains to connected automated mobility, and (f) Q.9 pertains to

low-emission vehicles. Note: Items a, b, and c are detailed in Table 2; (*)

indicates that the respondents do not find answers among the options provided,

while (**) indicates no answer was given

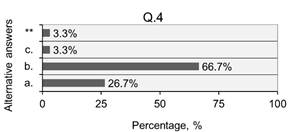

Regarding the responses to the question Q.4 (see

Fig. 12c) about "road infrastructure", they reveal important insights

into how people perceive the concept. Most respondents (67%) associated road

infrastructure with the road networks and roads within the context of land

transportation. This suggests that the concept primarily evokes the idea of

connectivity and the organizational structure of transport systems,

highlighting their role in promoting travel and commerce. On the other hand, around

27% of the responses linked the term to the materials used for creating stable

and durable road surfaces. This indicates an awareness of the technical aspects

of road construction, acknowledging that the quality of materials is crucial

for the longevity and safety of roadways. It is also noteworthy that two

respondents associated road infrastructure with both options (i.e., a and b in

Fig. 12c), reflecting a more comprehensive understanding of the topic that

encompasses both the physical elements and the broader network of routes. The

exclusion of skyscrapers (see Q.4, option c in Table 2) in their associations

highlights a clear delineation between structures and infrastructure (i.e.,

only one respondent selected option c for Q.4 in Table 2). Respondents likely

view road infrastructure as distinct from building construction, focusing on

transportation rather than urban architecture. In turn, the fact that one

respondent did not provide an answer could suggest either a lack of familiarity

with the topic or ambiguity in the understanding of road infrastructure,

indicating that public knowledge on this subject may vary, which ideally it

should not.

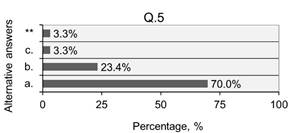

Regarding the question, 'What is an autonomous

vehicle?' (Q.5), Fig. 12d shows that 70% know that an autonomous vehicle is a

car capable of sensing road conditions and driving without human intervention;

additionally, 23% imagined that it is a vehicle that belongs to a single owner;

one respondent associated it with a vehicle designed exclusively for the

transportation of heavy goods and hazardous materials, while one respondent did

not answer this question. However, 57% were not willing to use an autonomous

vehicle, while the remaining respondents were equally divided between being

willing to test an autonomous vehicle and expressing uncertainty (see Q.6 in

Table 2). The high percentage of respondents recognizing autonomous vehicles as

self-driving suggests growing awareness of advanced technologies. However, the

reluctance to use them (57%) may stem from safety concerns, mistrust in

technology, or lack of understanding about their reliability. The varied

perceptions, from ownership to specific use cases, highlight a need for better

public information and outreach to address misconceptions and enhance

acceptance of autonomous vehicles.

Confirming the understanding of shared mobility

from Q.3, in Q.7 in Table 2, 57% of respondents associated the concept of

car-sharing services with option (b), which involves renting vehicles for short

periods, sharing the costs, and facilitating bookings through an app or

website. Meanwhile, 37% associated it with "a support service for the

purchase of zero-kilometre vehicles", while the remaining respondents did

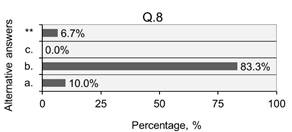

not answer. Furthermore, concerning Q.8 in Fig. 12e about connected and automated

mobility, 83% answered the question indicating that connected mobility uses

technologies for real-time communication, while automated mobility employs

autonomous vehicles. Meanwhile, 10% incorrectly attributed it to means of

promoting congestion, and only two respondents did not answer. Appropriately,

none associated it with bikes. The understanding of connected mobility

emphasizes awareness of technology’s role in communication, while

misattributions to congestion reflect a possible lack of comprehensive

knowledge. The absence of bike associations may indicate overlooked

alternatives in mobility solutions.

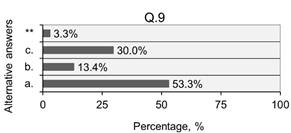

Regarding Q.9 in Fig.

12f, 16 respondents stated that a low-emission vehicle is powered by gas or

bi-fuel, electric, or hybrid engines (option “a” in Table 2), while only 4

indicated that it is a vehicle that can operate solely on solar energy (option

“b” in Table 2). Nine respondents incorrectly identified it as a vehicle that

consumes more fuel than traditional models (option “c” in Table 2), and one

respondent did not answer. The varied responses to Q.9 indicate a general

awareness of low-emission technologies, but misconceptions about solar energy

and fuel consumption persist, highlighting the need for improved education on

sustainable vehicle options.

Regarding Q.10 in Table

2, 93% of respondents linked micromobility to light vehicles for short city

trips, such as e-scooters, showing strong awareness of modern urban transport

options, while the remaining respondents did not provide an answer. About 73%

were not willing to receive the questionnaire via email, while the remaining

respondents were evenly split between giving a positive answer and choosing not

to answer (see Q.11 in Table 2). The reluctance to participate via email

suggests potential privacy concerns or preferences for different communication

methods, highlighting the need for varied engagement strategies. Despite the small sample size, the insights

offered are valuable, emphasizing the importance of effective communication

about infrastructure development to better engage the public and assess the

social impact of novel technologies integrated in transport services and road

design. Future efforts should expand the sample to identify broader

relationships and involve experts, as well as explore other methods to reach

the target respondents.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Starting from

data-driven trend analysis, road infrastructure is crucial for sustainable

urban mobility, requiring investments in public transport, bicycle lanes, and

pedestrian areas to reduce congestion and pollution. Incorporating smart

technologies enhances traffic management and safety, while multimodal solutions

– combining transit, cycling, walking, and eco-friendly fuels – improve

accessibility and urban quality of life. Prioritizing pedestrian-friendly

infrastructure and supporting emerging technologies like autonomous vehicles

and ridesharing promote cleaner air and digital communities. As Italy’s

mobility concepts evolve, inclusive policies that consider diverse groups,

especially the elderly, are essential to assess their social impact. Engaging

older adults through surveys provides valuable insights into their awareness,

attitudes, and experiences, ensuring their active participation and preventing

marginalization in sustainable and smart mobility initiatives.

Do the Elderly Know It's

Sustainable Mobility? This study sheds light on elderly respondents'

perceptions of sustainable and smart mobility. Most participants were aged

65-75, with many holding only a high school diploma, suggesting potential links

between age, education, and understanding of modern mobility concepts. Given

the level of education of the respondents and the number of correct answers,

the understanding of the topic is quite good. While 83% recognized smart

mobility as environmentally friendly and digitally enhanced, misconceptions

still existed, such as associating it with speed or limited terminology

familiarity. Knowledge about road infrastructure, autonomous vehicles, and

connected mobility varied; some correctly identified key features, but gaps

remained, like linking traffic congestion to connected mobility or

misunderstanding low-emission vehicle capabilities. A notable 57% were hesitant

to use autonomous vehicles, mainly due to safety and trust concerns,

highlighting the need for better public education. The high awareness of

micromobility (93%) indicates openness to urban solutions. However, reluctance

to engage via email underscores privacy concerns, emphasizing the importance of

diverse communication channels for effective outreach.

Despite the small sample

and provisional nature of the questionnaire, these findings emphasize the

critical importance of implementing targeted communication and education

strategies to improve understanding and acceptance of sustainable and smart

mobility. Developing inclusive policies is essential to ensure that innovative

mobility solutions address the diverse needs of all groups, especially

vulnerable populations. Such policies help prevent marginalization, promote

social equity, and foster greater societal participation.

Future research

involving larger, more diverse samples and expert input in questionnaire design

will support the development of comprehensive, culturally sensitive outreach

strategies. Promoting inclusivity strengthens social cohesion and guarantees

that sustainable mobility benefits everyone, contributing to more resilient and

equitable urban environments.

Acknowledgements

This research has

been partially supported by the European Union - NextGenerationEU – National

Sustainable Mobility Center CN00000023, Italian Ministry of University and

Research Decree n. 1033 –

17/06/2022, Spoke 9, CUP B73C22000760001. The authors also thank the interviewees for

the spontaneity with which they embraced our initiative.

References

1.

Papadakis Dimitrios Minas, Andreas Savvides,

Michael Aimilios, Apostolos Michopoulos. 2024. „Advancing sustainable urban

mobility: insights from best practices and case studies”. Fuel Communications 20. 1-18. ISSN: 2666-0520. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfueco.2024.100125.

2.

Banister David 2018. „The sustainable mobility

paradigm”. Transport Policy 15(2): 73-80. ISSN: 0967-070X. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.10.005.

3.

Elassy Mohamed, Mohamed Al-Hattab, Maen Takruri, Sufian

Badawi. 2024. „Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart

cities”. Transportation Engineering 16:1-18. ISSN: 2666-691X. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.treng.2024.100252.

4.

Zhao

Hongduo, Difei Wu. 2015. „Definition,

Function, and Framework Construction of a Smart Road”. In: New Frontiers in Road and Airport Engineering, edited by Lijun Sun, Jianming Ling, Hongduo Zhao,

Feipeng Xiao, Baoshan Huang, 204-218. Reston, Virginia: American Society of

Civil Engineers (ASCE). ISBN: 9780784479483.

5.

Angelidou Margarita, Christos Politis, Anastasia Panori,

Thomas Bakratsas, Katharina Fellnhofer. 2022. „Emerging smart city,

transport and energy trends in urban settings: Results of a pan-European

foresight exercise with 120 experts”. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change 183: 1-17. ISSN: 0040-1625. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121915.

6.

Dingil

Ali Enes. 2025. „Fostering inclusive urban transportation in planning and

policy-making: An umbrella review using ALARM methodology”. Sustainable

Futures 9: 1-10. ISSN: 2666-1888. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2024.100420.

7.

Tafida

Adamu, Alaloul Wesam Salah, Zawawi Noor Amila Bt Wan, Musarat Muhammad Ali,

Abubakar Adamu Sani. 2024. „A Re-view

of Eco-Friendly Road Infrastructure Innovations for Sustainable

Transportation”. Infrastructures, 9(12): 1-43. ISSN 2412-3811. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures9120216

8.

Burlacu Alina Florentina, Emily Tan. 2022. „How Do Best

Performing Countries in Road Safety Save Lives on the Roads? Lessons Learned

from Case Studies in Singapore”. In: Advances in Road

Infrastructure and Mobility. IRF 2021. Sustainable Civil Infrastructures, edited by Akhnoukh Amin, Kaloush Kamil, Elabyad Magid, Halleman Brendan, Erian Nihal, Enmon

II Samuel, Henry Cherylyn, 117-133. Switzerland: Springer. ISBN: 3030798011.

9.

Pompigna Andrea, Raffaele Mauro. 2022. „Smart

Roads: A State of the Art of Highways Innovations in the Smart Age”. Engineering

Science and Technology. An International Journal 25: 1-15. ISSN: 2215-0986. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2021.04.005.

10.

Yusuf Syed Adnan, Arshad Khan, Riad Souissi. 2024.

„Vehicle-to-everything (V2X) in the autonomous ve-hicles domain – A technical

review of communication, sensor, and AI technologies for road user safety”. Transportation

Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 23:1-23. ISSN: 2590-1982. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100980.

11.

Zare Nazanin, Elzbieta Macioszek, Anna Granà, Tullio

Giuffrè. 2024. „Blending

Efficiency and Resilience in the Performance Assessment of Urban Intersections:

A Novel Heuristic Informed by Literature Review”. Sustainability

16(6):1-24. ISSN: 2071-1050. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062450.

12.

Guo Mingyuan, Sepani Senaratne, Laura Almeida, Srinath

Perera. 2024. „Towards

Circularity in Roads Infrastructure: A Critical Review”. In: Circular Economy for Buildings

and Infrastructure. Sustainable Development Goals Series, edited by Zuo Jian, Shen

Liyin, Chang Ruidong, 319-331. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN: 978-3-031-56240-2.

13.

Directorate-General

for Mobility and Transport. „The official portal for European data”. Available

at: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/eu-transport-in-figures-2020?locale=en.

14.

ISTAT. „Indicators of the Vehicle Fleet”. Available at: https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/indicatori-del-parco-veicolare-anno-2023/.

15.

ISTAT. „Environmental data in cities”. Available at: https://www.istat.it/informazioni-sulla-rilevazione/dati-ambientali/.

16.

Berrada

Jaâfar, Hassan Mahdavi S.M., Romina Quaranta, Paola Rodríguez, Victor Ferran, Jenny

Weidenauer. 2025. „Driving the Future: Unveiling Innovative

Business Models for Shared Automated Mobility Services”. In: Shared Mobility Revolution. Lecture Notes in Mobility, edited by Cornet Henriette, Gkemou M aria, 199-214.

Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN: 978-3-031-71792-5.

17.

Ting Hua

Ting, Lee Lai Soon, Stefan Pickl, Hsin-Vonn Seow. 2021. „Shared

Mobility Problems: A Systematic Review on Types, Variants, Characteristics, and

Solution Approaches”. Appl. Sci. 11(17): 1-42. ISSN: 2076-3417. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/app11177996.

18.

Narayanan

Santhanakrishnan, Constantinos Antoniou. 2023. „Shared mobility services towards Mobility as a Service

(MaaS): What, who and when?”. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and

Practice 168: 1-15. ISSN:

1879-2375. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2023.103581.

19.

National

Observatory on Sharing Mobility. „8th National Report on Shared Mobility”.

Available at: https://osservatoriosharingmobility.it/.

20.

Morimoto

Akinori, Ailin Wang, Nahoiro Kitano. 2022. „A conceptual framework for road

traffic safety considering differences in traffic culture through international

comparison”. IATSS Research 46(1): 3-13. ISSN: 0386-1112. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2021.11.012.

21.

European

Commission. „Road safety policy framework 2021-2030”. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0407_EN.html.

22.

ISTAT. „Road crashes in Italy”. Available at: https://www.istat.it/tag/incidenti-stradali/.

23.

ISTAT. „Resident population”. Available at: https://demo.istat.it/.

Received 30.06.2025; accepted in revised form 10.09.2025

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License